What is RAM?

We explain what RAM is and how it differs from other types of computer memory

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

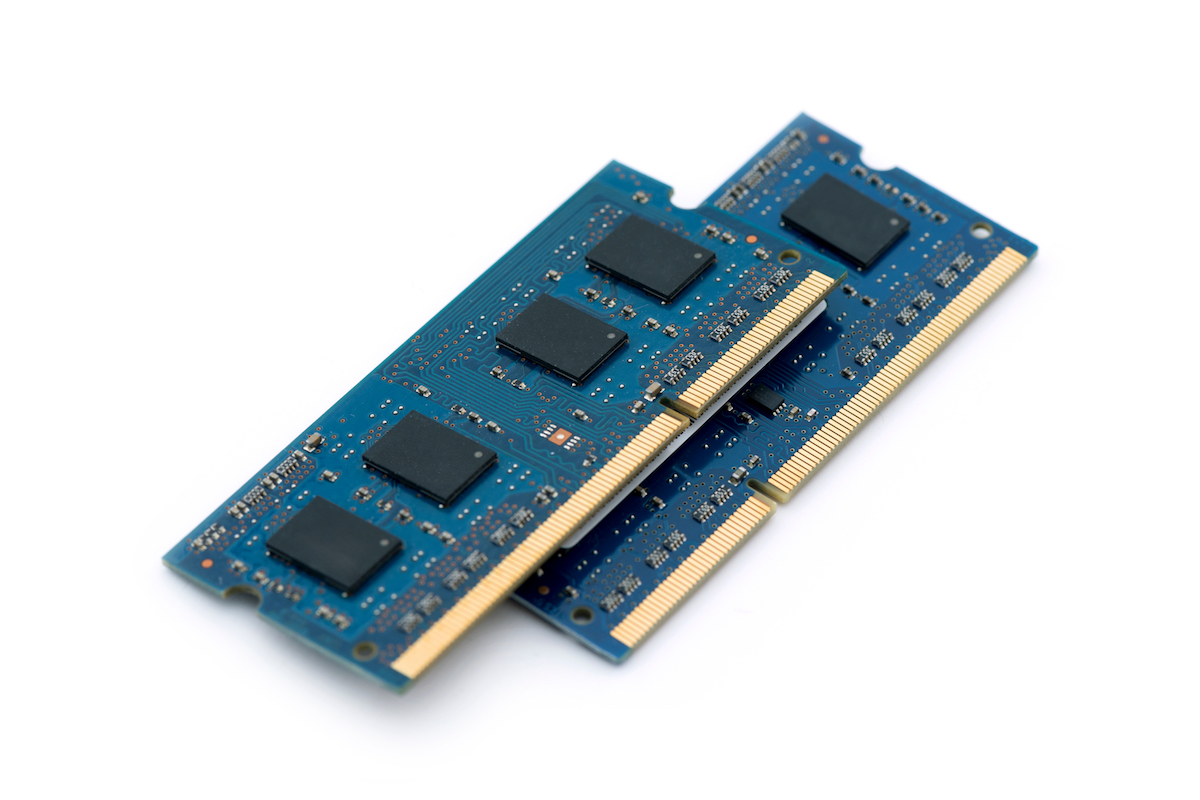

Random-access memory (RAM) enables a device, whether a smartphone, tablet, computer or anything else that needs to read and write commands, to operate efficiently and complete operations quickly.

It's a short-term memory, enabling processes to both written and read to at the same time, making it a completely different type of memory compared to a hard drive or solid-state drive (SSD), known as direct-access memory. Unlike direct-access memory, when the power is removed the memory is completely wiped. Not something you would want to happen to the hard drive of a device.

Because of its unique nature, the data handled by RAM is continually changing and only processes the tasks needing to happen at any given moment. Anything else will be deferred.

But new RAM modules are currently being developed that could allow for other tasks to be stored, which means some operations, such as system startup, could happen much quicker as those actions are ready to be triggered.

The history of RAM

Although modern computers are completely different to those in existence half a decade ago, RAM was still present in many of the first computers, although up until the 1970s, the most commonly used method was magnetic core memory very different to the embedded circuitry RAM we know of today.

Dynamic Random Access Memory (DRAM) wasn't introduced until the 1970s (although as a concept, it was announced in 1968) and allowed data to be stored in transistors that were refreshed every few milliseconds, which remains to be used today.

How does RAM work?

RAM stores data in the form of ones and zeros (binary) in electrically powered transistors to enable fast access to every bit of data.

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

Unlike a traditional hard drive with spinning platters, RAM doesn't record data to a magnetic medium, so doesn't have a substantial "seek time" when data is demanded. But RAM needs to stay powered to retain this data, whereas a disk drive retains data even when powered off.

Types of RAM

Devices available today like laptops and tablets are often fitted with either static RAM (SRAM) or dynamic RAM (DRAM). The former is expected to lead to faster performance with less power consumption, given that data is kept in a six-transistor memory cell as. This is against DRAM which uses a transistor and capacitor in conjunction to establish what data is stored.

SRAM is, however, more costly to manufacture and so DRAM is the most widely-used form of memory architecture fitted into most devices.

DDR4 is the most common form of RAM found, although legacy devices will have been fitted with DDR3 or DDR2 iterations. The most recent breed of RAM is faster than its predecessors, which will come as no surprise, and features design tweaks. The implications for this centre on not being able to replace DDR3 RAM in a machine with the newer DDR4 version.

The future of RAM

Development is currently underway on RAM that can store data for much longer and won't even require the use of power. Researchers in China have also invented a form of memory that draws from aspects of RAM and read-only memory (ROM) that remembers tasks for as long as a user specifies.

The Optane drive, developed by Intel, combines the volatility of SSDs with the read and write speeds of RAM. This technology, if developed further is expected to replace both RAM and ROM in the future. Expanding RAM modules is also on the horizon for researchers, with a greater capacity allowing for more amounts of information to be stored - and more tasks running at the same time.

The far less abstract DDR5 RAM, however, is expected to hit consumer and business devices in the near future. Although little is known as to the exact specifications, this next-gen type of memory is expected to double the read/write speeds against the current DDR4.

Keumars Afifi-Sabet is a writer and editor that specialises in public sector, cyber security, and cloud computing. He first joined ITPro as a staff writer in April 2018 and eventually became its Features Editor. Although a regular contributor to other tech sites in the past, these days you will find Keumars on LiveScience, where he runs its Technology section.

-

Organizations hit by 90 zero-day vulnerabilities last year

Organizations hit by 90 zero-day vulnerabilities last yearNews Google Threat Intelligence researchers warn that edge devices and security appliances are prime entry points

-

Major data leak forum taken down

Major data leak forum taken downNews LeakBase enabled the sale and purchase of a huge amount of personal data and had more than 142,000 members