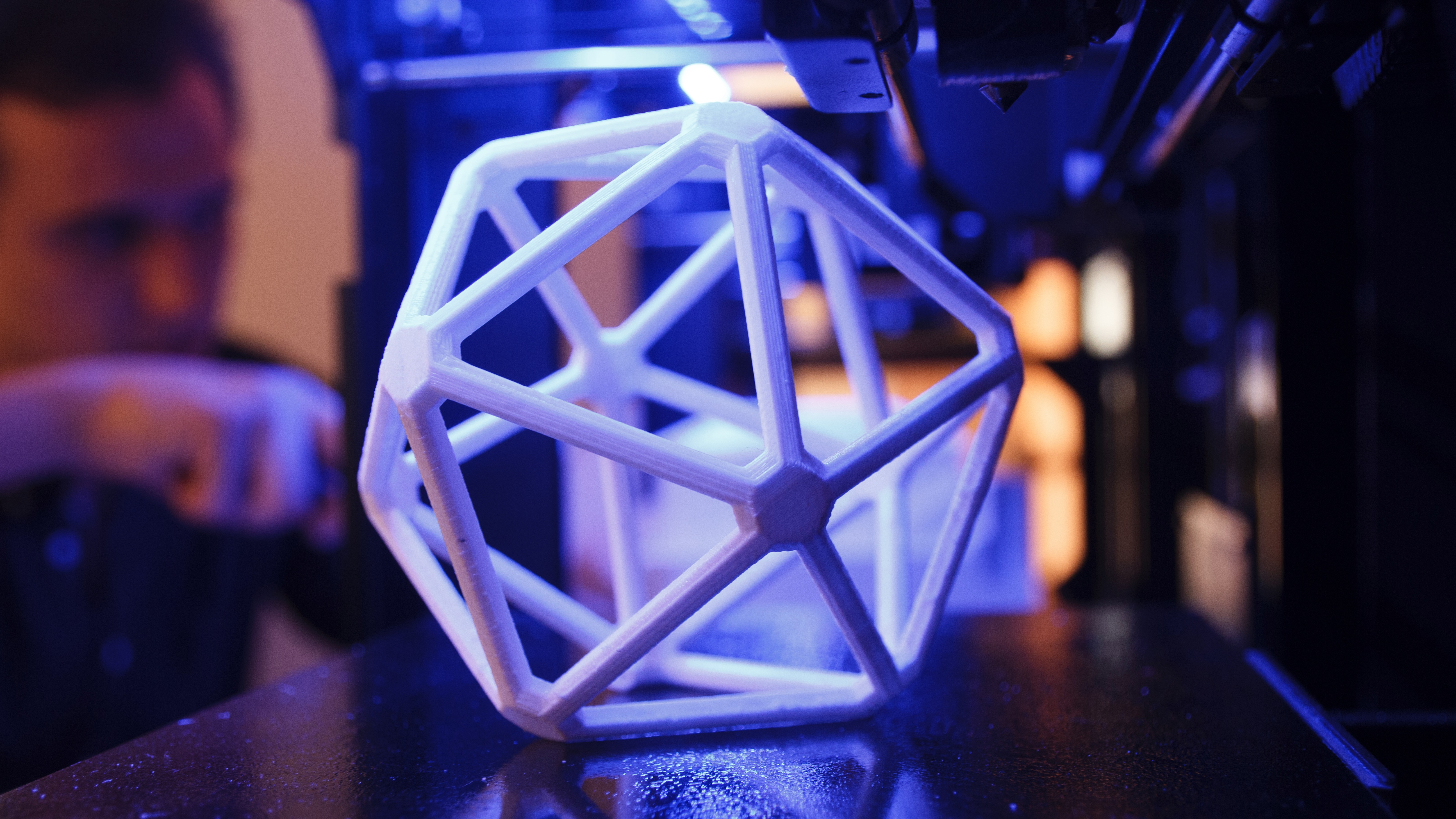

3D printing is finally coming of age

With 3D printing technology maturing – and getting more affordable – now anyone can get started with 3D printing

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

3D printing used to be the next big thing – but then the bubble burst. Early adopters struggled with unreliable hardware and janky software tools.

A 2013 feature in the Independent newspaper asked, “How hard can 3D printing really be?” – and concluded, “Quite hard”. Even trying out the nascent technology for yourself was expensive and fiddly: the printer tested by the Independent tipped the scales at £1400, and required a fair amount of self-assembly. Some years later, there are a host of use cases for 3D printing, with the pandemic and even the war in Ukraine giving a fresh lease of life to the once-bumbling technology.

Indeed, things have been steadily improving. Today you can pick up a lightweight 3D printer like the Easythreed Nano Plus for less than £100, or the larger Etina Tina 2 for just £50 more. Printer manufacturer UltiMaker recommends a budget of between $100 and $400 (£84 - £338) for a basic printer, with hobbyist machines going up to $1,000 (£840).

You might still need to bolt some parts together yourself, but this should be straightforward compared to assembling a first-generation 3D printer.

What materials do you need to buy?

Just as a regular printer needs ink, a 3D printer needs materials to print with. There’s a wide choice of materials to choose from: they may come in the form of powders, liquids, or solids, but by far the most common form is spools of thin plastic cable, in all colors of the rainbow. Some materials are tough, rigid, and flame-resistant, while others are flexible and rubber-like.

RELATED RESOURCE

Welcome to the 3D Generation: Unleash your creativity

Taking you through the innovation of 3D design

It’s worth noting the cheapest printers won’t be able to work with the full range of materials. A pricier model will not only work with a wider range of materials, but it may also offer automatic multi-material printing, switching between materials as it prints to produce complex models (commonly referred to as “parts”) that combine different colors, textures, and physical properties.

It’s still possible to create parts like this with a cheaper single-material printer – you just need to load up the right materials to print each section individually, and manually attach them all together at the end of the process.

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

Downloading and designing parts

If you want to design and print your own custom parts, the difficult bit isn’t likely to be putting the printer together – it’s creating 3D computer models of the shapes you want to produce. Thankfully, you don’t need to start from scratch: there are huge libraries of downloadable online templates which you can draw on. The standard format, accepted by almost every 3D printer and modelling app, is Standard Triangle Language (STL), also known as Standard Tessellation Language.

You’re not limited to reproducing other people’s creations, however. You can make simple adjustments, such as customising the dimensions and appearance of parts to your own particular needs. To really maximise the potential of your printer, you can learn how to design your own parts from scratch – ensuring you’re never restricted to choosing from whatever you can find online, and can produce unique objects, precisely tailored to your requirements.

What can I print with a 3D printer?

3D printers come in all shapes and sizes: larger printers are likely to have bigger print areas, meaning they can produce large items in a single operation. Even so, outside of industrial settings, not many 3D printers are capable of producing models much more than 30cm in any direction.

That doesn’t mean you can’t print something large – the trick is to break the model down into smaller parts, print them in sequence, and glue or slot them together by hand. However, we’d recommend that for your first few projects you stick within the bounds of the build chamber, until you get familiar with the behaviour of your printing system, and the material.

Nik Rawlinson is a journalist with over 20 years of experience writing for and editing some of the UK’s biggest technology magazines. He spent seven years as editor of MacUser magazine and has written for titles as diverse as Good Housekeeping, Men's Fitness, and PC Pro.

Over the years Nik has written numerous reviews and guides for ITPro, particularly on Linux distros, Windows, and other operating systems. His expertise also includes best practices for cloud apps, communications systems, and migrating between software and services.

-

Stop treating agentic AI projects like traditional software

Stop treating agentic AI projects like traditional softwareAnalysis Designing and building agents is one thing, but testing and governance is crucial to success

-

PayPal appoints HP’s Enrique Lores in surprise CEO shake-up

PayPal appoints HP’s Enrique Lores in surprise CEO shake-upNews The veteran tech executive will lead the payments giant into its next growth phase amid mounting industry challenges