British ISPs fight to make the web less secure

Why Britain’s broadband providers are worried about a new technology that guards against online snooping

British broadband providers are fighting a technology that's designed to make internet connections more secure to prop up their own, outdated content filtering systems.

The British ISPs' trade body, the Internet Service Providers Association (ISPA), dubbed Mozilla a "villain" for supporting DNS-over-HTTPS (DoH). The technology replaces the current, insecure DNS system, which leaves consumers open to snooping and man-in-the-middle attacks that could result in computers being infected with malware when a user attempts to visit a legitimate site.

However, British broadband providers are launching a rearguard action against DoH because it knocks out their ability to track users' surfing habits and operate the filters that prevent them visiting blacklisted websites, such as those hosting child abuse images identified by the Internet Watch Foundation (IWF), or copyright infringements.

"I think ISPs were worried about the potential political backlash and wanted to get ahead of it," said Jim Killock. CEO of the Open Rights Group. "They are worried about other impacts on their networks."

ISPA on the attack

The issue came to the fore when ISPA named Mozilla as a finalist in its "Internet Villains" award category, accusing the software organisation of plans to "introduce DNS-over-HTTPS in such a way as to bypass UK filtering obligations and parental controls, undermining internet safety standards in the UK".

The award nomination quickly drew widespread condemnation, forcing ISPA to withdraw the nomination a few days later, claiming that it didn't "reflect ISPA's genuine desire to engage in a constructive dialogue" about DoH.

While the award may have been intended as light-hearted, it revealed what DoH might mean for the major broadband providers that ISPA represents, forcing them into costly replacements for the insecure DNS system they currently rely on for internet filtering.

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

"They realised that DoH might totally shaft that IWF list by its normal implementation and that any alternative is going to probably be even less effective, more easily bypassed and quite expensive," said Alex Bloor, of ISP Andrews & Arnold, which opted out of ISPA membership several years ago.

"The fact they have done this is a signal they realise that when an ISP is no longer its customers' DNS provider... it compromises a cheap and cheerful way of doing some blocking," Bloor continued.

The UK ISPs effectively use a hack to manipulate which pages are served when DNS requests are resolved, with blacklisted sites blocked by the ISP. But tech companies such as Google and Mozilla are keen to introduce DNS encryption because of growing security threats. In Google's words: "traditional DNS queries and replies are sent without encryption, making them subject to surveillance, spoofing, and DNS-based internet filtering".

Power shift

Anxious to make life as easy as possible for its members, ISPA despite a deluge of flack from the infosec community claims DoH isn't necessarily more secure than unencrypted traffic and would merely benefit the big tech firms. "DoH basically takes DNS resolution away from ISP providers and if you are tech minded you can do that already," said a company official in a phone interview.

"An aim of the DoH standard is that it standardises DNS resolution within a small number of largely American-owned companies. It's not in itself bad, but raises concerns over how we want to run the internet."

Other concerns for ISPs are a reduction in network monitoring capabilities and breaking captive portals used for signing into networks, but the main weapon against DoH is the "think of the children" argument.

The major ISPs are obligated to provide blocks and they accept that it's part of their role since Conservative campaigners such as Claire Perry MP pushed for greater online censorship. Having paid to put the controls in place, ISPs don't want to face another costly bill to replace the insecure systems.

"Back then we had Claire Perry... and we thought it was all a mad idea but the industry has moved on and they recognise that if you want to run a large-scale consumer ISP business in the UK you need to provide parental controls that's part of the operating license that you need in the UK," said the official.

The stance echoes that of one of ISPA's main partners, the IWF, of which ISPA was a founding member. The companies both use the services of Political Intelligence, a political lobbying firm (see "Who's behind ISPA?", opposite). "We don't want to demonise technology, but the way in which DNS-over-HTTPS is being implemented is the problem," the IWF said in a statement.

"It would have a catastrophic impact... not just busting the IWF's block list but swerving filters, bypassing parental controls, and dodging some counter-terrorism efforts as well," the IWF claimed.

"We want to see a duty of care placed upon DNS providers so they are obliged to act for child safety and cannot sacrifice protection for improved customer privacy," it continued.

Browser backdown?

The furore does seem to have bought the broadband providers some time. Mozilla was planning to switch on DoH by default in its Firefox browser, but now says it won't do that to give the British broadband providers more time to work on alternative filtering systems.

"We are pleased that as a partial response to some of our work in the UK, Mozilla did say 'we are not going to role out DoH by default in the UK' because we don't think that would have been the right thing to do," ISPA said.

However, there's a feeling that the UK is being left behind, with Mozilla "currently exploring potential DoH partners in Europe to bring this important security feature to other Europeans more broadly". Mozilla declined to comment on whether it had bowed to pressure in the UK.

On top of that, in a fresh draft posted to the Internet Engineering Task Force on 8 July, days after the ISPA furore, Mozilla engineers outlined plans to allow broadband providers to take back control of DNS resolution.

"A network operator might be obligated to provide a filtering policy to users of its network," the engineers wrote. "Because such a policy is often enforced by the network operator's default resolver, the use of a technology such as DoH can result in bypassing local policies.

"If the user agent can check for the presence of a policy, this could be used as a signal that the network operator wishes its resolver to be used as a condition of using the network, and that DoH should be disabled."

-

Redefining resilience: Why MSP security must evolve to stay ahead

Redefining resilience: Why MSP security must evolve to stay aheadIndustry Insights Basic endpoint protection is no more, but that leads to many opportunities for MSPs...

-

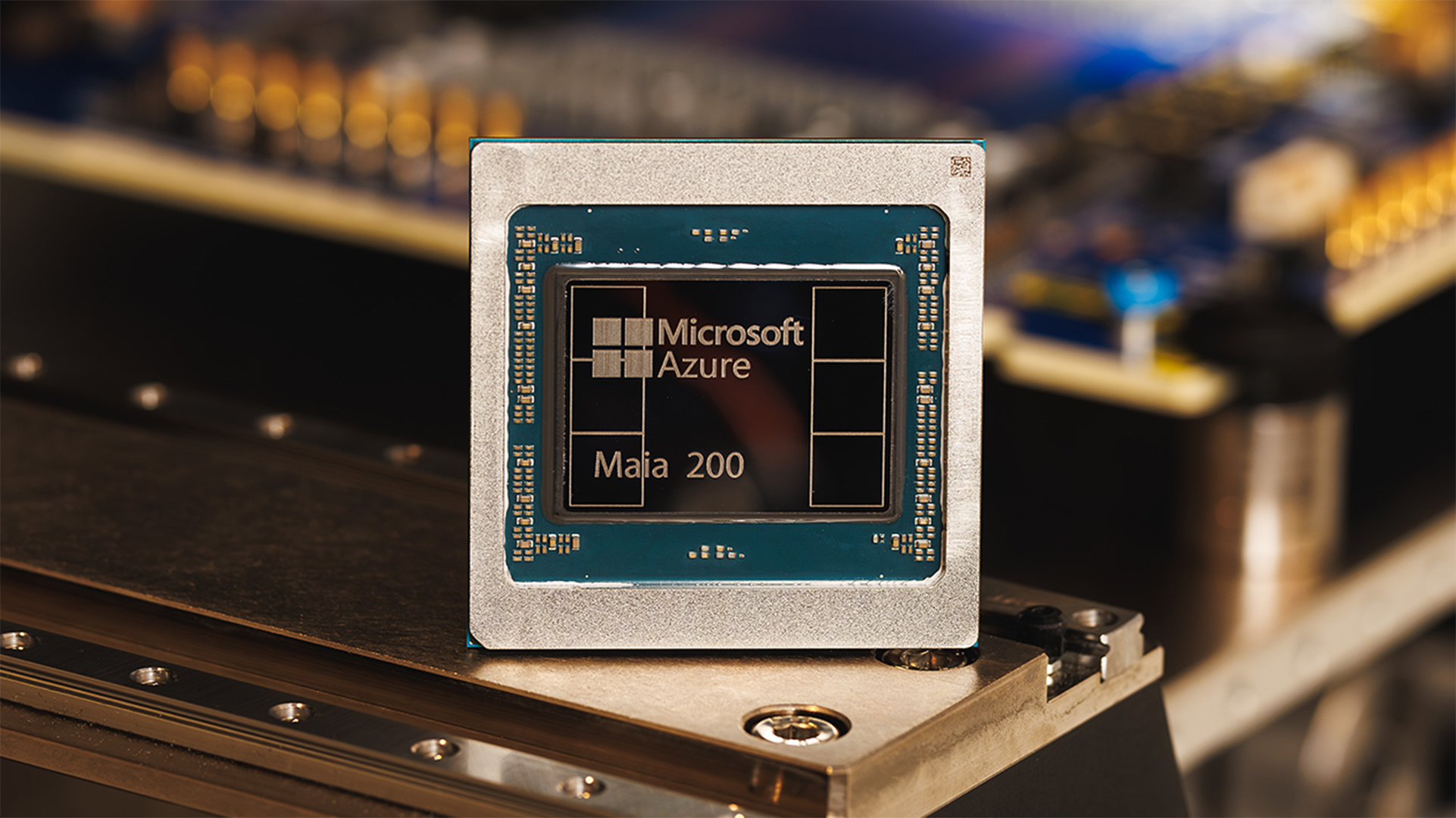

Microsoft unveils Maia 200 accelerator, claiming better performance per dollar than Amazon and Google

Microsoft unveils Maia 200 accelerator, claiming better performance per dollar than Amazon and GoogleNews The launch of Microsoft’s second-generation silicon solidifies its mission to scale AI workloads and directly control more of its infrastructure