How can we protect the mental health of cyber security staff and CISOs?

The pressure is mounting on cyber staff and behavioural changes and additional support is required from the business

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

When Nominet’s second annual CISO stress report was released earlier this year, the most striking figure was the huge jump from 27% of CISOs stating that work stress had a detrimental impact on their mental health in 2019 to 48% in 2020.

“There’s a divide between the expectations the board has of CISOs and the ability of CISOs to actually achieve those,” Stuart Reed, VP of Nominet says.

Gary Foote, CIO of the Haas F1 team, who effectively takes on the CISO role too, says that the findings from the survey were alarming.

“Half of the stress that CISOs take is the lack of understanding upwards in the food chain – they’re the subject matter experts in a world that very few people understand. They’re having to prevent anything that might happen to the organisation and also effectively try and be a crystal ball to gaze into the future,” he states.

The weight on a CISO’s shoulders is having a detrimental impact on their relationships, on their work, and even on their physical health. While the CISO may be feeling a huge amount of stress, they are not alone, particularly in cases where a company has been hacked or suffered from a data breach. Last year, Equifax’s CISO of Europe, David Rimmer, explained how, during one of the biggest data breaches ever his team worked 36 hour shifts and were placed under huge pressure that would ultimately affect their mental health.

Taking all this into account, what more should organisations be doing more to support their cyber security staff?

The relationship between cyber security and mental health

In the last five years or so the topics of IT security and mental health have independently come to the fore as important business issues, finally garnering the mainstream attention they have sorely deserved.

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

While change is often slow in business, there are encouraging signs on both fronts. However, there has been little thought given to how they interact with each other, meaning making any specific arrangements for cyber security staff in the case of a data breach, or indeed reducing a CISO’s responsibility and workload on a day-to-day basis, have often not been considered.

For businesses, the reality is that a lack of focus on mental health can pose a risk on a par with many other vulnerabilities. Ameet Jugnauth, head of IT risk and governance at Lloyds Banking Group, explains: “If you’re not focusing on your people – and that includes their mental health – then that is a weakness in your defence”.

Nathan Hayes, IT director at Osborne Clarke, puts it another way: “If we don’t take care of our people, they won’t take care of our business”.

The solution

As both cyber security and mental health are incredibly complex with so many different factors at play, it’s difficult to find a solution that works for all businesses, or even all employees within the same business. But some organisations are trying to instil the foundations of a mental health programme – and applying it to their cyber teams.

Law firm Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer has trained senior members of staff to deal with and identify mental health issues within their teams. In addition the company has focused on a ‘behaviours campaign’, which is particularly important for the IT security team.

“One thing you don’t want is pointing fingers in the middle of an incident response – you need to be working on it professionally together,” says the organisation’s CISO Mark Walmsley.

The company also has both internal and external coaches on how to deal with stress and identify particular crisis situations.

RELATED RESOURCE

The IT Pro Podcast: How do we fix security?

We discuss why firms keep making the same security mistakes with guests Graham Cluley and Stu Peck

“They come in and say ‘this is what resiliency looks like’ so that you’re not in a place where your stress becomes a mental health problem,” says Walmsley.

Often the pressure isn’t only coming from the organisation – but stems from the individuals themselves.

“When we’ve had incidents in the past, the individuals felt like they had messed-up and it’s really important they don’t feel that way. If they feel blamed they’re less likely to flag issues, so it’s important to encourage a ‘don’t blame culture’,” says Osborne Clarke’s Hayes.

Wayne Smith, Birmingham Airport’s IT and information security director, adds: “[Cyber security teams] take a lot of pride in their job and want to do the best job they can. So when something bad happens, they feel like they’ve let people down or they’ve let the organisation down and they will beat themselves up internally.”

When the airport has had an incident in the past, Smith, who isn’t an IT security expert himself, says his main job has been to provide moral support to staff.

“It’s about getting them coffee, getting bacon sandwiches in and giving the guys moral support, as well as deflecting any of the stuff that’s coming from other managers. We have a response plan where anyone outside of the team talks to me, and I talk to the team and we keep it separate to reduce the pressure on them,” he says.

Freshfields, meanwhile, has a shift rota that comes into place if an incident occurs.

“This means it’s not me and you in there for 36 hours trying to work it out – we have three shifts for people to do with a 10 hour shift, with a handover period of two hours, so you can go and grab a rest, have some food and speak to family [when it’s not your shift],” Walmsley explains.

“If you expect people to do anything longer than a 15 or 16 hour shift it’s not sustainable beyond a couple of days – they start to become negative about the environment and are tired, they start making odd decisions after a while,” he adds.

British Red Cross’ head of information security, Lee Cramp, takes a leaf out of the way fire services respond to emergencies – by practicing scenarios.

“The more practice you have, when the inevitable happens, then the mental health side of it and the pressure becomes second nature. That doesn’t mean there’s not an impact on individuals and we would support them when it does happen, but we try to minimise that impact beforehand by pre-planning through simulated attacks,” he states.

Other factors at play

According to the Nominet research, CISOs are working 10 or so extra hours a week – equating to £23k worth of extra time per year – and 90% of them would be willing to take a 7.76% pay cut – an average of £7,475 per year – if it improved their work-life balance.

It’s likely that CISOs aren’t the only staff having to work extra hours as a result of more of a focus on cyber security – IT staff, IT security staff, and risk management will all also be putting in extra hours. This is exacerbated during a breach as the company needs staff to work around the clock to fix an issue. Foote believes that the pressure involved in cyber incidents is enormous because every other department is relying on technical experts to get the company out of a crisis.

“Everyone is looking at you to get it solved but it’s still new to everyone and with recent vulnerabilities you don’t have research to fall back into – if you were a marketeer with an issue you can fall back on previous research,” he says.

It’s crucial then, to not only put in place simulations, mental health awareness programmes and train senior members of staff to act as mental health helpers, but to ensure that the root of where much of the stress, pressure and blame comes from is altered. That means more manageable workloads, hours, responsibilities and increasing collective responsibility, communication and support.

-

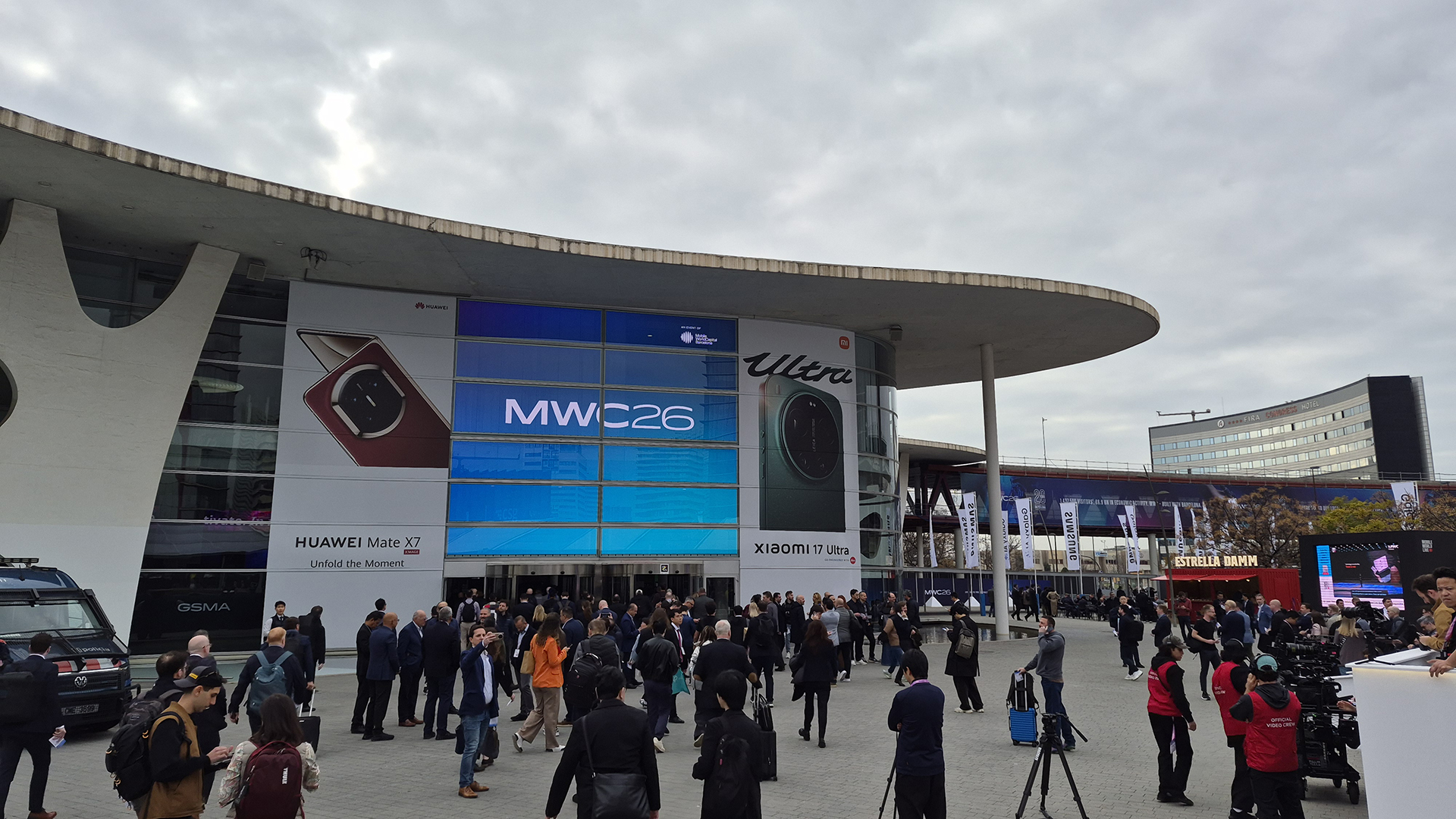

Give businesses more practical AI services and some return on investment before you go selling 6G

Give businesses more practical AI services and some return on investment before you go selling 6GThe value of modular computing and community-led development wins big at MWC, while AI continues to consume us all

-

Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella says 'anyone can be a software developer' with AI

Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella says 'anyone can be a software developer' with AINews AI will cause job losses in software development, Nadella admitted, but claimed many will reskill and adapt to new ways of working