Will Trump go nuclear over cyber warfare?

That the US president loves The Bomb is no secret, but would he use it to hit back against a cyber attack?

Anyone who has been feeling nostalgic for the 1970s and '80s will have had their flare and electronica-filled dreams rudely interrupted this month by a less welcome visitor from the past the threat of nuclear war.

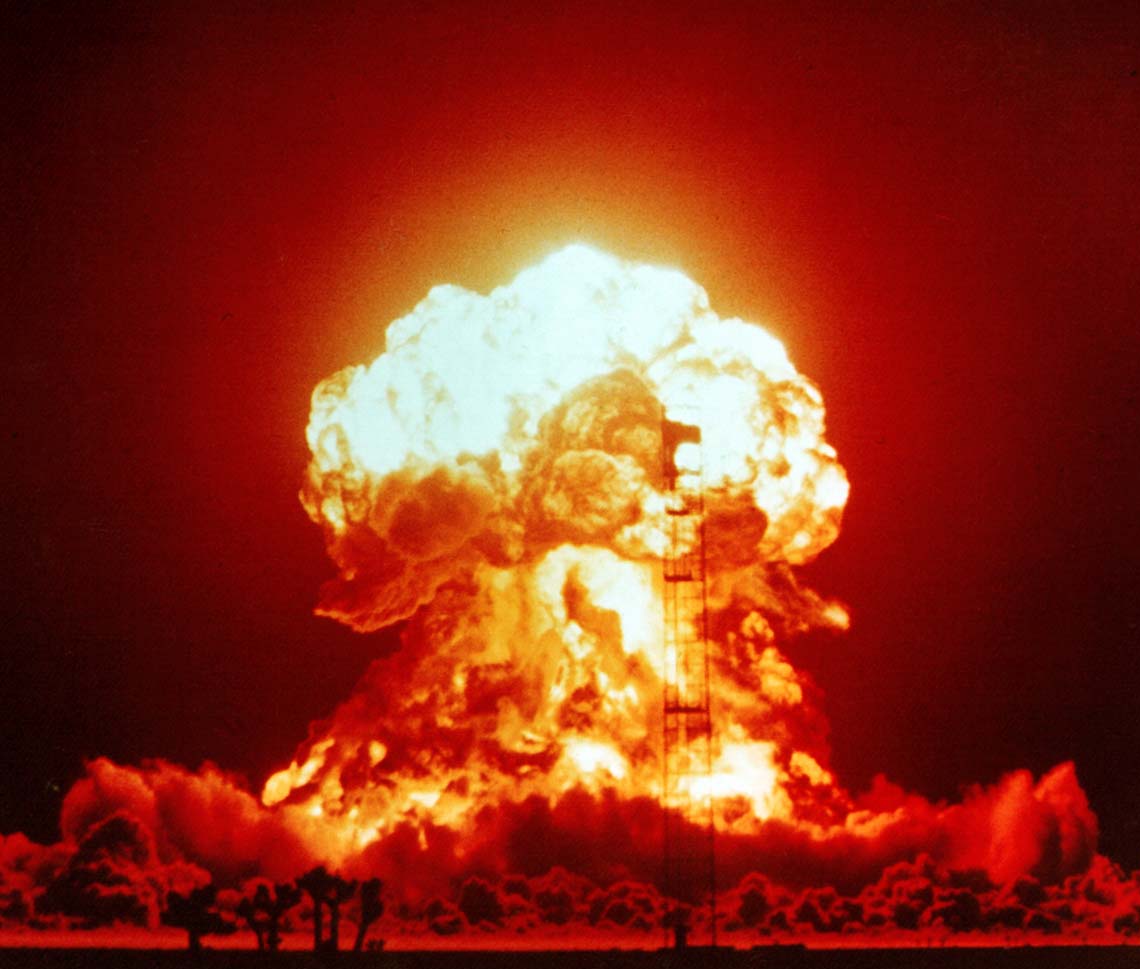

To be fair, this particular mushroom cloud has been looming on the horizon for a while: towards the end of last year, US president Donald Trump and North Korean dictator Kim Jong-Un entered into a very public 'mine's bigger than yours' missile-waving contest.

The State of the Union Address this week also offered further insight into just how enamoured Trump is with becoming Death, the Destroyer of Worlds, with a promise to bolster the country's nuclear arsenal.

But it was the suggestion that the US could launch a nuclear first-strike against a country that causes a serious cyber attack on national infrastructure that really caught my eye.

It was the Huffington Post that first reported on a leaked official paper that suggested the country could retaliate against a non-nuclear strategic attack with nuclear weapons, expanding the remit of the "nuclear deterrent".

"For US deterrence to be effective across the emerging range of threats and contexts, nuclear-armed potential adversaries must recognize that their threats of nuclear escalation do not give them freedom to pursue non-nuclear aggression," the document reads.

"The United States would only consider the use of nuclear weapons in extreme circumstances ... [which] could include significant non-nuclear strategic attacks. Significant non-nuclear strategic attacks include, but are not limited to, attacks on the US, allied, or partner civilian population or infrastructure, and attacks on U.S. or allied nuclear forces, their command and control, or warning and attack assessment capabilities."

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

What does this mean? Well, historically this has included things like biological or chemical attacks, meaning if a nation state used chlorine bombs on the US population, the US could (and perhaps would) retaliate with nukes.

The New York Times suggests, however, that this could now include "devastating" cyber attacks, citing several national security experts.

Could the nuclear deterrent legitimately be used as a cyber-deterrent, then? I'm not convinced.

First, let's acknowledge that cyber attacks, particularly those carried out by nation states, are potentially devastating. The BlackEnergy malware attacks on Ukraine were sophisticated, but even more low-tech incidents, such as a DDoS attack, can have a significant impact just ask the citizens of Lappeenranta.

But using a nuclear weapon to retaliate against such an attack is like using a sledgehammer to kill a fly. Yes, cyber attacks can be extremely disruptive, but they are generally speaking not destructive and don't result in mass casualties.

Nuclear attacks, by contrast, are designed to inflict the greatest amount of damage as possible, which also means killing as many people as possible. If anything, they're the opposite of the quiet sabotage caused by cyber attacks.

What's more, attribution is a really difficult subject when it comes to cyber attacks do you really want to lob an ICBM at another country thinking they carried out an attack when you can't be sure? Of course, said country and/or their allies would likely retaliate in kind, leading to a global nuclear armageddon and I'm pretty sure we all decided we didn't want that way back at the height of MAD.

As much as cyber warfare gets sexed-up, the truth is it's subtle, non-destructive (at least not on a mass scale) and is frequently reversable.

There's a type of person who prefers perhaps even yearns for the imposing silhouette of a shining, heavy duty conventional weapon. When they think of protection and retaliation, they think of launch countdowns and explosions and it seems the US is fully onboard with this vision, which is odd for a country that has been thwarted again and again by asymmetric warfare. But the reality is that cyber weapons are more strategic and can be extremely disruptive, without culminating in open warfare with millions dead.

A final thought: of all the countries that should know the power of cyber weapons over conventional ones when it comes to achieving geopolitical aims, it's the US. While there's never been any official confirmation (and there probably never will be), it's widely thought that the Stuxnet virus was crafted as a joint enterprise by US and Israeli special forces. It damaged nuclear centrifuges in a way that was so subtle it took years to be detected peacefully achieving the desired outcome of stymying Iran's efforts to enrich uranium. The irony that the US would retaliate against such an effort on its own soil with a nuclear bomb isn't lost on me.

Jane McCallion is Managing Editor of ITPro and ChannelPro, specializing in data centers, enterprise IT infrastructure, and cybersecurity. Before becoming Managing Editor, she held the role of Deputy Editor and, prior to that, Features Editor, managing a pool of freelance and internal writers, while continuing to specialize in enterprise IT infrastructure, and business strategy.

Prior to joining ITPro, Jane was a freelance business journalist writing as both Jane McCallion and Jane Bordenave for titles such as European CEO, World Finance, and Business Excellence Magazine.