Keep cool and be efficient

Powerful portable PCs are only possible thanks to innovative components that run cool and quiet. Here’s what led to their creation.

The portable computer wasn't made possible by any single technology, but a whole host that developed in parallel over time. The gradual shift from valves to transistors to integrated circuits helped shrink computers from room-sized cabinets into something that could sit on a desk, for example, but it took leaps and bounds in battery and display technology before one could fit into something that was smaller than a suitcase.

Even so, prioritising size always meant that portable computers were much less powerful than their desktop counterparts. The need to keep cases small and light enough to carry meant big batteries were out of the question, which in turn meant so were the latest power-hungry processors unless you didn't mind being near-permanently tethered to a power outlet, that is. Even storage space lagged behind because notebook-size hard drives couldn't match the capacity of a 3.5in desktop drive. The list of compromises goes on and on.

Dealing with heat

But one other design constraint that's often overlooked is the need to keep components cool. Desktop PCs can deploy huge heatsinks and large, rapidly spinning fans to keep cool air circulating, with any components that run red hot kept safely separated in a generously proportioned case. Not so with a notebook.

Cooling fans can be used in a compact PC designed for use on the move, but there's seldom room for ones much larger than a 50p piece and they can't spin too quickly if noise is to be kept within tolerable levels. That means heat needs to be dissipated through the case, but no one wants a notebook that warms their hands or burns their thighs when they're working. So it's back to square one, with slower components that don't generate as much heat and don't need much in the way of cooling.

Why Moore's Law matters

This situation started to change as the limits of Moore's Law came into view. In 1965, Intel co-founder Gordon Moore anticipated that the number of transistors making up a processor would double every 12 months.

The law' has so far stood, but the schedule has been gradually stretched in the 50-year interim and now stands at something like every two years, not least because the laws of physics are starting to limit the number of transistors that can be crammed onto a tiny slice of silicon.

So rather than try to make processors do more with more, chip designers have long since adopted the alternative approach of doing more with less. The quest to shrink transistors ever smaller is far from over, but processor architecture is now as much about increasing efficiency as anything else and this has some important implications for mobile PCs.

But efficiency matters more

Key among these is the reduced reliance on clock speed for performance. High GHz ratings used to be the best measure for how powerful a PC was, but the advent of processors with multiple cores and even single cores that can seemingly do two things at once have dramatically reduced its relevance. And with lower clock speeds come lower operating temperatures, so cooling requirements are reduced accordingly.

Better onboard power management also means a little battery goes a very long way, which has obvious benefits for portable computers that spend extended spells away from power sockets, but processors aren't the only component to consider. All of the above also applies to graphics chips, which in some cases are even incorporated into the main processor for even greater energy efficiency, and storage has seen similar improvements.

For example, the gradual shift from power-hungry hard drives to solid-state storage with no moving parts not only benefits battery life, but also physical design. Even a 2.5in portable hard drive needs a similar size drive bay to sit in, while the handful of tiny chips that comprise a solid-state drive can be hidden almost anywhere.

Portability without compromise

Notebook PCs have been getting thinner and lighter for a few years thanks to these kinds of improvements, but now the same kind of compromise-free performance can be squeezed into a tablet.

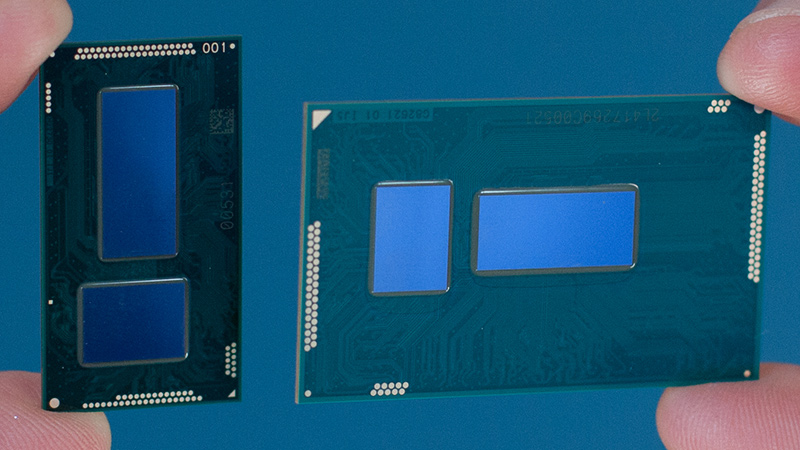

The 5th Generation Intel Core M that powers the HP Elite x2 1011, for instance, contains two processor cores and some 1.3 billion transistors, but it's still no larger than a fingernail. There's up to 512GB of fast solid-state storage, too, not to mention Intel HD Graphics 5300 that make everything from presentations to rather less productive pursuits run smoothly.

So despite being just 10.7mm thick and weighing a mere 780g when detached from its keyboard dock in tablet mode, the HP Elite x2 1011 still packs the power of a full PC. Windows 10 also runs all of your essential business software, so you won't be left in the lurch just because you want to travel light. And with HP's leading security and manageability features, the HP Elite x2 1011 will deliver peace of mind, too.

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

-

Researchers call on password managers to beef up defenses

Researchers call on password managers to beef up defensesNews Analysts at ETH Zurich called for cryptographic standard improvements after a host of password managers were found lacking

-

Is there a future for XR devices in business?

Is there a future for XR devices in business?In-depth From training to operations, lighter hardware and AI promise real ROI for XR – but only if businesses learn from past failures

-

HP ProBook 4 G1a review: A no-frills business machine for the average office

HP ProBook 4 G1a review: A no-frills business machine for the average officeReviews A serious but dull business laptop, however, HP's ProBook 4 is a decent middle-tier machine

-

The HP ZBook Ultra G1a offers truly impressive levels of performance – a genuine game-changer

The HP ZBook Ultra G1a offers truly impressive levels of performance – a genuine game-changerReviews AMD's new Ryzen AI Max+ 395 redefines what we can expect from a laptop chipset with an integrated GPU and delivers outstanding performance

-

The HP ZBook X G1i is a full-throttle juggernaut – you couldn't ask for much more from a workstation

The HP ZBook X G1i is a full-throttle juggernaut – you couldn't ask for much more from a workstationReviews The HP ZBook X G1i offers almost everything you could want from a workstation, and it's delightful to use

-

HP ZBook 8 G1ak 14 review: Plenty of promise but falls short

HP ZBook 8 G1ak 14 review: Plenty of promise but falls shortReviews This portable mobile workstation promises so much but fails to deliver in a few key quarters – meaning it's hard to justify its price tag

-

We're in the age of "mega-tasking," and here's what HP is doing about it

We're in the age of "mega-tasking," and here's what HP is doing about itnews The world's first ultrawide conferencing monitor and a Nvidia-powered workstation aim to tackle our growing work demands

-

The HP OmniBook X Flip 16 is a brilliant, big, beautiful 2-in-1 laptop – but it's also an absolute bargain

The HP OmniBook X Flip 16 is a brilliant, big, beautiful 2-in-1 laptop – but it's also an absolute bargainReviews HP pairs a gorgeous OLED touchscreen with a smart 2-in-1 design – the result is a superb everyday laptop for sensible money

-

AI PCs are paying dividends for HP as firm reports sales surge

AI PCs are paying dividends for HP as firm reports sales surgeNews HP has pinned recent revenue increases on Windows 11 and AI PC sales

-

The HP OmniStudio X is a powerful, design-led all-in-one for creative work – but it could do with a stronger GPU

The HP OmniStudio X is a powerful, design-led all-in-one for creative work – but it could do with a stronger GPUReviews HP's answer to the iMac is a premium all-in-one that blends powerful performance with sleek design