Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The Metropolitan Police's controversial facial recognition technology trial has proved fruitless, it has emerged. Police have revealed that the scheme, intended to help identify and apprehend violent criminals, resulted in zero arrests.

The facial recognition equipment in question was positioned on a prominent pedestrian bridge, with a view to deploying the technology in a bid to identify criminals. Meanwhile, critics of the plan cited human rights law, calling upon the police to cease a practice that they believed constituted an institutionalised invasion of privacy.

Scotland Yard has not disclosed how many people in total were questioned at the behest of the technology, but did reveal that it hadn't led to a single arrest. "This deployment formed an important part of ongoing trials and a full review of its use will take place once they have been completed," explained Detective Superintendent Bernie Galopin, the Metropolitan Police's lead for the technology.

"It is important to note all the faces on the watchlist used during the deployment were of people wanted by the Met and the courts for violence-related offences," he went on. "If the technology generated an alert to signal a match, police officers on the ground reviewed the alert and carried out further checks to confirm the identity of the individual [...] All alerts against the watchlist will be deleted after 30 days and faces in the database that did not generate an alert were deleted immediately."

Scotland Yard said that the Stratford operation would be "overt", with police informing passersby of the cameras' presence, both audibly and with leaflets. However, upon observation, The Independent found no such practice being adhered to. Many pedestrians simply did not register the posters emblazoned around the targeted area.

Meanwhile, privacy activists, including the titanic advocacy group Liberty, have widely denounced the scheme, with some dubbing it "staggeringly inaccurate". Opponents are keen to avoid the fate of the US, where facial recognition tech is used much more prevalently to hunt down criminals; indeed, just last week the fate of alleged mass shooter Jarod Ramos was sealed in Annapolis, after his image was fed into the Maryland Image Repository System (MIRS).

It's not hard to see why activists are resisting the move so vehemently; back in May, it was found that a shocking 98% of the Met's facial recognition technology was inaccurate. Not only would this serve to embroil innocent people in criminal cases, but could lead police to prematurely relinquish dangerous suspects. Even when the false positives are omitted from the system, the ethical dilemma do we really want to ramp up surveillance on unwitting citizens? endures.

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

For his part, Detective Superintendent Galopin is treating the experience as a learning curve: "The [Stratford] deployment formed part of the Met's ongoing trial of the technology, and was used to further assess how it can support standard policing activity and assist in tackling violent crime," he explained. "We will now consider the results and learning from this use of the technology."

Given divisiveness that such facial technology elicits, we're glad to see the Met is treading cautiously. Whether facial recognition technology will bridge the gap from smartphone security gimmick to state-sponsored surveillance tool remains, for now, a mystery.

-

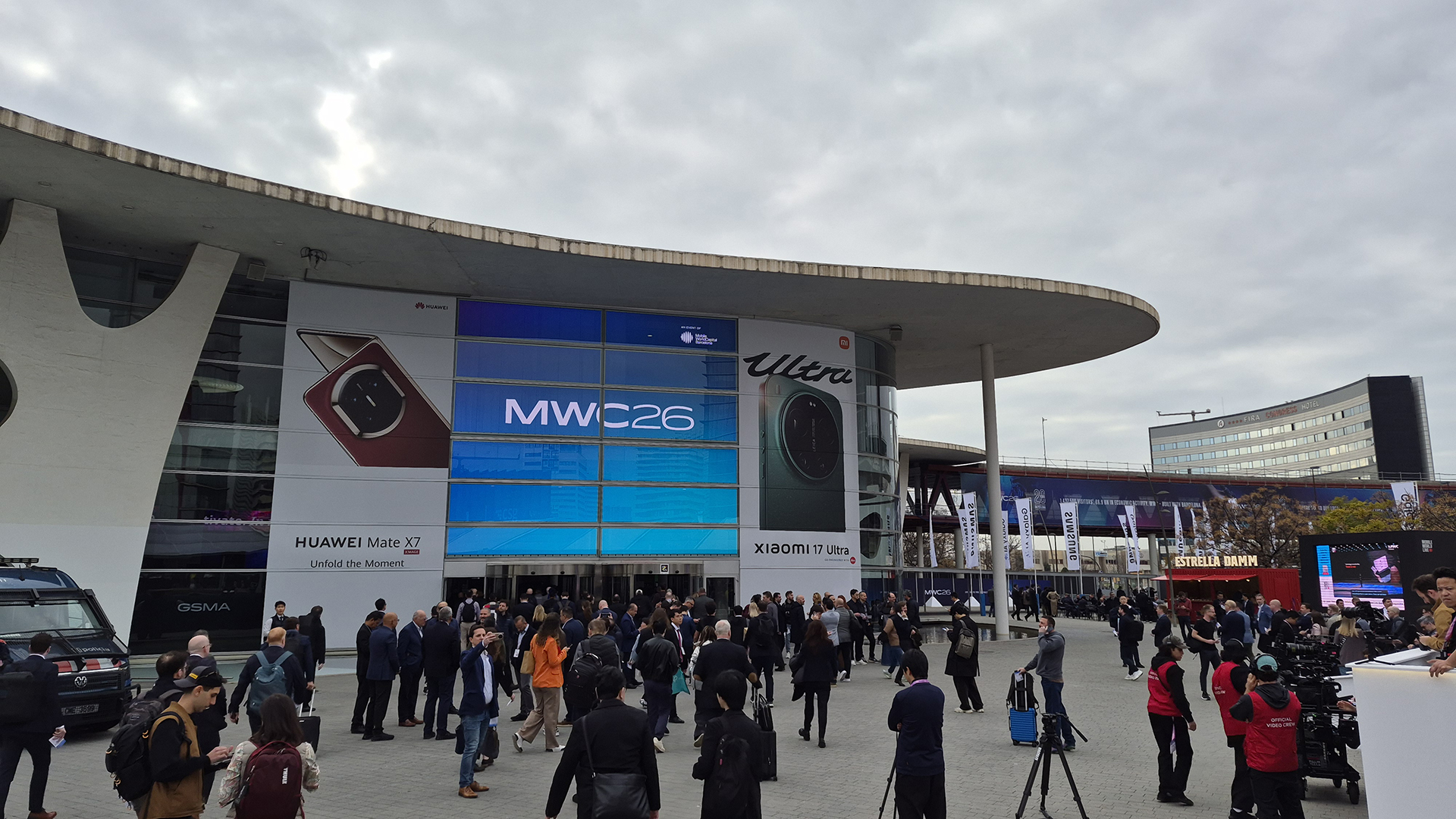

Give businesses more practical AI services and some return on investment before you go selling 6G

Give businesses more practical AI services and some return on investment before you go selling 6GThe value of modular computing and community-led development wins big at MWC, while AI continues to consume us all

-

Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella says 'anyone can be a software developer' with AI

Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella says 'anyone can be a software developer' with AINews AI will cause job losses in software development, Nadella admitted, but claimed many will reskill and adapt to new ways of working