Why WPA3 may be no safer than WPA2

Dragonblood vulnerabilities mean KRACK attacks are here to stay

WPA3, also known as Wi-Fi Protected Access 3, was introduced by the Wi-Fi alliance in June 2018 and is now mandated for use in all devices that connect to a wireless network. The standard is the third and current generation of the Wi-Fi Protected Access (WPA) security certification program, which first became available in 2003.

Its release in 2018 came after security researchers uncovered a significant flaw in its predecessor, WPA2. This attack was named KRACK, short for Key Reinstallation Attack, and allowed hackers to steal data, including login credentials, private chats and credit card information, transmitted over networks.

Secure your Wi-Fi against hackers in 10 steps Apple and Google begin patching “devastating” Wi-Fi exploit Choose the right wireless AP for your business

Improving over WPA2, and in a bid to prevent such attacks, the current standard brings new capabilities to improve cyber security in networks, combining the secure encryption of passwords and enhanced protection against brute-force attacks to safeguard home Wi-Fi connections - ideal at a time when a large majority of the workforce are working from home as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, despite these enhanced security protections, it turns out that WPA3 might not be more secure than WPA2 after all.

The WPA2 KRACK attack

The KRACK attack was discovered by researcher Mathy Vanhoef in 2016, and works by exploiting the four-way handshake protocol used by numerous cryptographic methods including the WPA2 standard.

When a client device (like a laptop or smartphone) wants to join a network, the four-way handshake determines that both the client device and the access point have the correct authentication credentials, and generates a unique encryption key that will be used to encrypt all the traffic exchanged as part of that connection.

This key is installed following the third part of the four-way handshake, but access points and clients allow this third message to be sent and received multiple times, in case the first instance is dropped or lost. By detecting and replaying the third part of the four-way handshake, attackers can force the reinstallation of the encryption key, allowing them to access the packets being transmitted.

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

RELATED RESOURCE

Simplify cluster security at scale

Centralised secrets management across hybrid, multi-cloud environments

What actions the attacker can carry out depends on which subset of the WPA2 encryption standard is in use. If the victim is employing AES-CCMP encryption, then packets transmitted by the victim can be decrypted and read, allowing the theft of sensitive information. Vanhoef warns that "it should be assumed that any packet can be decrypted".

This also allows the decryption of TCP SYN packets, which can then be used to hijack TCP connections and perform HTTP injection attacks, such as infecting the target with malware.

If the target is using WPA-TKIP or GCMP (also known as WiGig), the potential damage is even worse. In addition to decryption, key reinstallation allows hackers to not only decrypt and read packets, but also to forge packets and inject them into a user's traffic. WiGig is particularly vulnerable to this.

Dragonblood WPA3 vulnerabilities

WPA3 was supposed to address the security shortcomings of the WPA2 standard, and the most notable change was the introduction of the 'Dragonfly' handshake.

A type of handshake officially known as the 'simultaneous authentication of equals' handshake (or SAE for short), Dragonfly uses forward secrecy to protect previous browsing sessions, along with a high-entropy pairwise master key to prevent password guessing.

However, in April 2019, Vanhoef and fellow researcher Eyal Ronen published a paper detailing five flaws in the standard, which the researchers are terming 'Dragonblood'. This was followed by the discovery of two additional flaws in August.

Dragonblood attacks exploit a range of vulnerabilities, including forcing WPA3-compatible devices to downgrade to WPA2 and then launching the KRACK attack against them, altering the handshake to force access points to use weaker cryptography, and exploiting side-channel leaks to gain information about the network password, which can then be used to brute-force it.

Following the disclosure of the "devastating" flaw, the Wi-Fi Alliance rushed out a software fix to protect against it "These issues can all be mitigated through software updates without any impact on devices' ability to work well together," the WiFi Alliance said.

Thankfully, this didn't result in an updated version of the standard being issued. An updated standard is not expected to be backwards-compatible with any pre-existing WPA3 devices. Vanhoef and Ronen have said that addressing these flaws is surprisingly hard and criticised the Wi-Fi alliance for developing the standard behind closed doors, instead of allowing the open source community to contribute to its development.

Will I have to buy new equipment?

Thankfully, the fix the WiFi Alliance released for Dragonblood didn't result in an updated version of the standard being issued. An updated standard is not expected to be backwards-compatible with any pre-existing WPA3 devices.

Adam Shepherd has been a technology journalist since 2015, covering everything from cloud storage and security, to smartphones and servers. Over the course of his career, he’s seen the spread of 5G, the growing ubiquity of wireless devices, and the start of the connected revolution. He’s also been to more trade shows and technology conferences than he cares to count.

Adam is an avid follower of the latest hardware innovations, and he is never happier than when tinkering with complex network configurations, or exploring a new Linux distro. He was also previously a co-host on the ITPro Podcast, where he was often found ranting about his love of strange gadgets, his disdain for Windows Mobile, and everything in between.

You can find Adam tweeting about enterprise technology (or more often bad jokes) @AdamShepherUK.

-

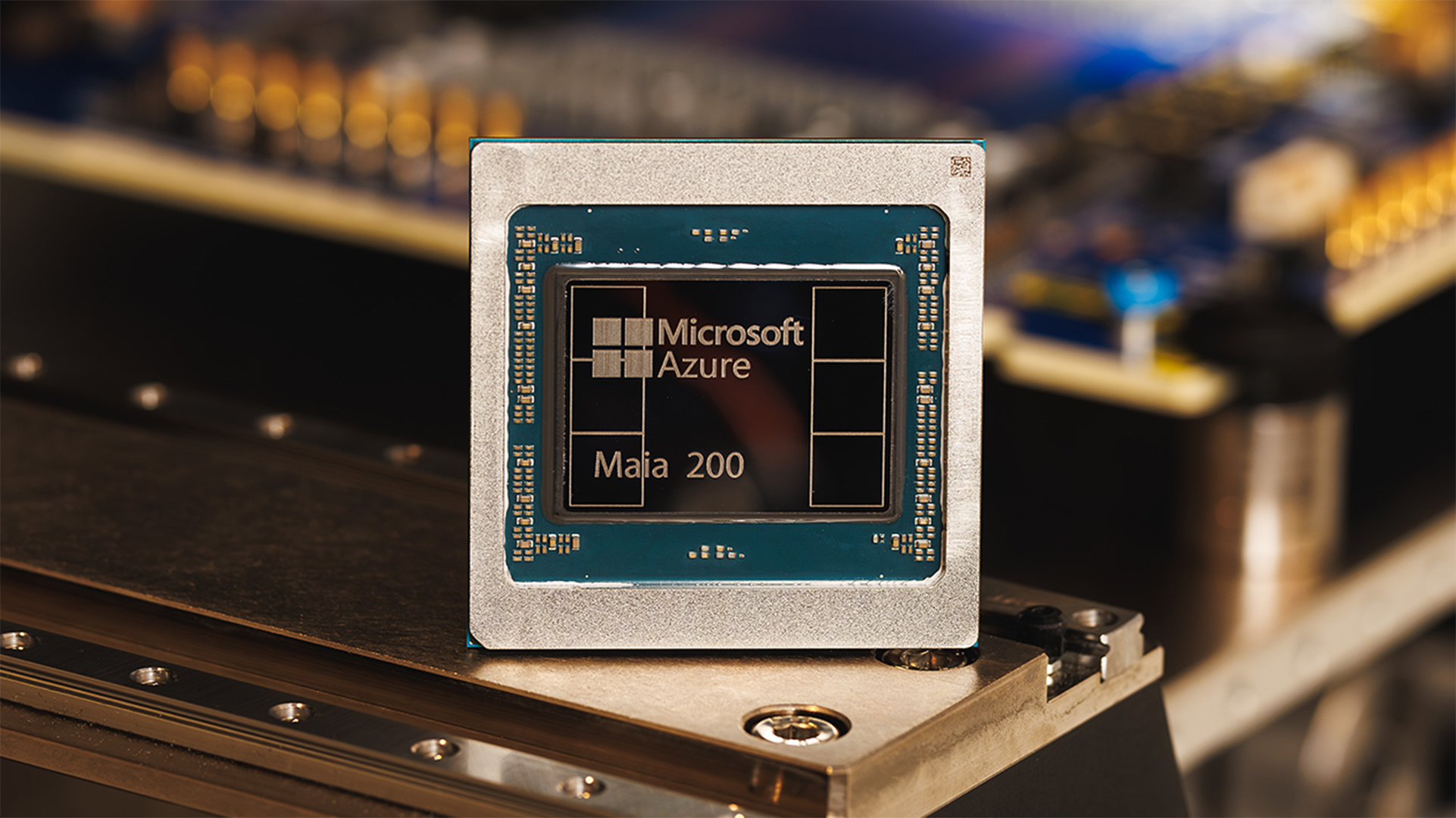

Microsoft unveils Maia 200 accelerator, claiming better performance per dollar than Amazon and Google

Microsoft unveils Maia 200 accelerator, claiming better performance per dollar than Amazon and GoogleNews The launch of Microsoft’s second-generation silicon solidifies its mission to scale AI workloads and directly control more of its infrastructure

-

Infosys expands Swiss footprint with new Zurich office

Infosys expands Swiss footprint with new Zurich officeNews The firm has relocated its Swiss headquarters to support partners delivering AI-led digital transformation