Should human augmentation technology be regulated?

The idea of becoming part person, part machine is exciting to many, but there are important ethical challenges

The year is 2027. Corporations have managed to develop human augmentation technology that divides society financially and morally. The advancement of artificial intelligence (AI) is set to not only bring vast economic inequality, but also a nano-virus pandemic and a subsequent financial crisis.

Sounds familiar? Although this is the basis of the plot of 2011’s Deus Ex: Human Revolution video game, it doesn’t seem too far off from the anticipated future.

In fact, human augmentation has been a part of our lives for some time now. From contact lenses to artificial knee replacements, chances are that you have encountered human augmentation before and even benefited from it yourself.

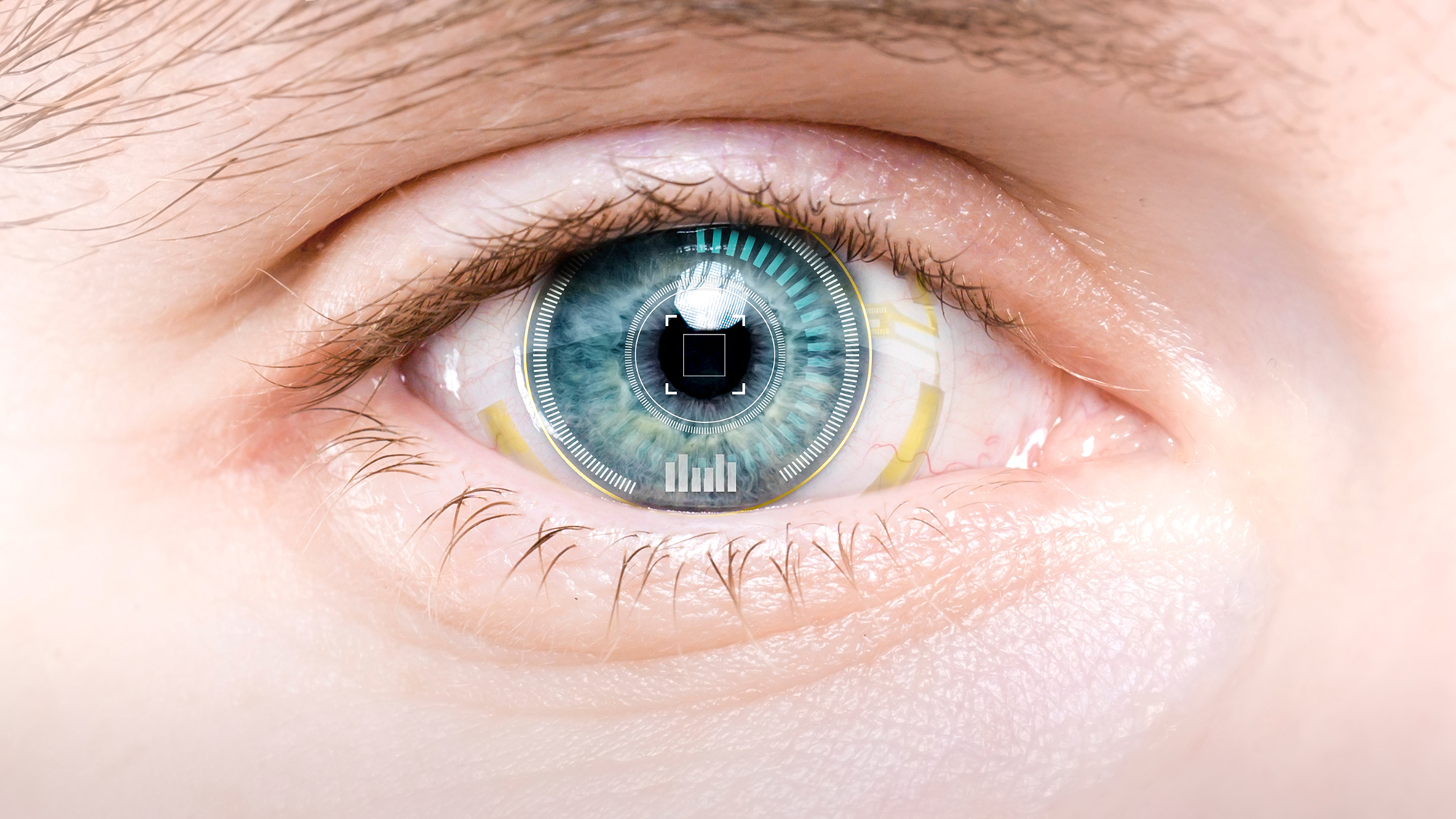

The development of new technologies is constantly shaping the potential of human enhancement. Although bionic arms might not be readily available at the moment, we might soon be able to connect with our friends and family in a blink of an eye – literally. In mid-September, eyewear giant EssilorLuxottica, the parent company of popular glasses brands such as Ray-Ban and Oakley, announced a multi-year partnership with Facebook with the aim of expanding the smart glasses market. While this might not sound too cyborg-esque at the moment, they may well be precursors to smart contact lenses or eye implants.

Amid all the excitement and innovation surrounding human augmentation, however, there are legitimate fears that if left unregulated, society might end up in a dystopian future straight out of a sci-fi video game.

According to bioethicist and Oxford University professor Julian Savulescu, companies developing human augmentation technology will prioritise profit over providing their customers with genuine benefits.

“A good example is fast food. It can be good and a part of a good life, but it’s in the interest of the companies to maximise the consumption of fast food, so they make it as addictive as possible,” he says.

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

That’s not the only danger stemming from the lack of regulation, warns professor Savulescu. General demand for human augmentation, when combined with the inherent drive to keep up with the Joneses, is likely to lead to an arms race.

“Many of the enhancements are what are called mixed positional and nonpositional goods,” he says. “Take memory, for example. Memory has a nonpositional benefit, which means it's good for me regardless of whether other people have or don't have it. I can remember the shopping when I go to buy things, or I can remember people's names. But it's also a positional good, which means it's good for me if I have it and other people don't. So you get what's called an arms race – for each person to have something that is better than another. One of the ways of protecting against that kind of arms race, is to have some kind of regulation or some sort of regulated market.”

It’s also feared that human augmentation technology could cause even greater inequality within society. A recent study commissioned by security firm Kaspersky Lab found that 69% of people worldwide believe only rich people will be able to enjoy access to the technology. In the UK, the number was even higher, with almost 8 in 10 (78%) of those surveyed agreeing that human augmentation technology will be limited to the rich.

History repeats itself

“Those who fail to learn from history are condemned to repeat it,” Winston Churchill once famously said, paraphrasing philosopher and writer George Santayana. Although Churchill’s speech was made over 70 years ago, it still rings true – even in the world of tech.

According to Kaspersky senior security researcher David Jacoby, human augmentation technology is repeating the same mistakes as the Internet of Things (IoT).

“One of the biggest problems with IoT is that there are no regulations,” he tells IT Pro.

“There's no legislation, there are no requirements, there's no audit, there's no nothing. When it comes to cars, or trains, or planes, or buildings, or whatever, we have legislation. We have ISO standards for this. And now, with [human] augmentations, are we going to make the same mistakes over again? Or should we just pause for a while and say: ‘okay, if this is a natural part of evolution, we should think about the history that we kind of left up in the past’?”

Numerous cases of IoT devices being hacked have made headlines, the most notable incidents involving baby monitors. These devices often include a camera that is placed in the child’s bedroom or playroom and connected to the WiFi. The footage is transmitted in real time onto the parent or caregiver’s smartphone, letting them monitor the child while they are in a different part of the house.

Only last year, in a scenario straight out of every parents’ nightmare, a hacker managed to access a baby monitor belonging to a Seattle family, using it to spy on and talk to the child. This was not a new occurrence, however, as similar incidents were reported in 2016 and 2013 – and there are likely to be many more which had not reached international headlines.

That’s why, when implanting technological devices into a human body, one should bear in mind that these too can be hacked.

As reported by CNN, in 2017, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) confirmed that some implantable cardiac devices – typically pacemakers and defibrillators – were found to have software vulnerabilities that allowed them to be potentially accessed by cyber criminals.

That is why legislators should take note of the potential dangers of human augmentation and create regulations that will ensure the security of people benefitting from the technology.

Becoming more human

However, while some worry about being hacked, others hack themselves.

Two years ago, Liviu Babitz was introduced to BBC Two’s Victoria Derbyshire’s programme as a ‘biohacker’ – someone who enhances the functionality of their body by ‘hacking’ it.

Today, Babitz is the CEO and co-founder of CyborgNest, a London-based company that intends to help people become “more human” and better connected to the planet using sensory enhancement devices, which it expects to start shipping in early 2021.

The product, called Northsense, is described as “a new sensory organ” that helps the wearer navigate their path through vibrations. It mimics an electronic device implanted in Babitz’s own chest which notifies him every time he faces north.

Babitz is technically on the opposite side of the debate table from Savulescu or Jacoby, as the head of a company that has the potential to profit handsomely from human augmentation technology. Nevertheless, he agrees the area urgently calls for regulation.

“I think that, with time, everything should be certified and regulated, because that will guarantee that people are getting safe and proper products,” he says.

However, Babitz disagrees that tech companies are responsible for creating inequalities between people.

“What I care about is creating a richer life experience for people,” he says. “Obviously you can never create a situation where everybody gets everything. I think that the fingers should be pointed at governments and those who lead us, and not at creators or inventors.”

The Kaspersky report found that one in two (52%) UK adults believe that human augmentation technology poses dangers to society. That’s probably why the UK is also the most in favour of the government regulating the technology, at 77%.

With such an overwhelming majority being in favour of regulation, it would be in favour of everyone – consumers, inventors, and bioethicists – for the UK government to introduce adequate regulation. But will they manage to do so before 2027?

Having only graduated from City University in 2019, Sabina has already demonstrated her abilities as a keen writer and effective journalist. Currently a content writer for Drapers, Sabina spent a number of years writing for ITPro, specialising in networking and telecommunications, as well as charting the efforts of technology companies to improve their inclusion and diversity strategies, a topic close to her heart.

Sabina has also held a number of editorial roles at Harper's Bazaar, Cube Collective, and HighClouds.