The poisonous rootkits rocking the security world

There are some seriously stealthy rootkits running on computers today. Tom Brewster investigates the extent of the problem...

It is the dark chameleon of the security world, the evil twin of Where's Wally?

Previous TLD versions loaded almost immediately after the OS booted up. Now, by going below the operating system, TDL-4 has become a powerful beast, able to hide dirty software on users' machines as it steals data before sending it back to command and control centre servers. Meanwhile, IT departments are left clueless.

Scary skills

Whilst TDL-4 is one of the most sophisticated and widespread rootkits around it infected over 4.5 million PCs in just three months earlier this year there are others with equally impressive skills.

Some have focused on exploiting hardware virtualisation technology and essentially pose as hypervisors. Once on a system, such rootkits host the targeted operating system as a VM, thereby intercepting machine interactions. It was what the Blue Pill concept imagined in 2006, the creators of which claimed was undetectable. Yet there have been no notable infections of such hypervisor rootkits in the wild.

Mebromi is one particularly terrifying piece of work that has made it onto actual machines, however. It is designed to infect the BIOS part of a machine the first software that loads when a PC is powered up. That's seriously low-level infection, beyond Ring Zero where anti-virus sits.

Detected on Chinese computers in September, the malware could infect the BIOS and then initiate more code to install another rootkit at the MBR and kernel levels.

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

The beauty/ugliness of Mebromi lies in its ability to re-infect on every system restart if it needs to. Even if anti-virus detects and cleans the MBR infection, it can be restored at the next startup when the malicious BIOS payload can overwrite the MBR code all over again. For an Advanced Persistent Threat (APT), this is the rootkit you want.

"It's really quite technical how they're doing this, but essentially what they want to do is hide their system processes and hide the bad things they want to do," said Kaspersky researcher Ram Herkanaidu.

"Even when Windows starts up, if you've got anti-virus or anything like that, because it is catching all the I/O requests and things like that, it can then give false information back. It's highly stealthy."

Thankfully for end users, Mebromi isn't likely to spread across the globe anytime soon. That's largely because of the complexity of a successful infection. Mebromi would have to be able to get inside all different versions of Award BIOS - used by Phoenix Technologies motherboards if it was to be truly useful to cyber criminals. Kernel-level or MBR infections like TDL can work on all PCs. If you were a cyber criminal, which kind would you punt for? It's a no-brainer.

Many will now be waiting for BIOS-infecting rootkits to emerge able to infect a wider range of systems, however. Looking at how diligently hackers have worked in the past few years, expect such noxious beasts to emerge in the near future.

Tom Brewster is currently an associate editor at Forbes and an award-winning journalist who covers cyber security, surveillance, and privacy. Starting his career at ITPro as a staff writer and working up to a senior staff writer role, Tom has been covering the tech industry for more than ten years and is considered one of the leading journalists in his specialism.

He is a proud alum of the University of Sheffield where he secured an undergraduate degree in English Literature before undertaking a certification from General Assembly in web development.

-

The modern workplace: Standardizing collaboration for the enterprise IT leader

The modern workplace: Standardizing collaboration for the enterprise IT leaderHow Barco ClickShare Hub is redefining the meeting room

-

Interim CISA chief uploaded sensitive documents to a public version of ChatGPT

Interim CISA chief uploaded sensitive documents to a public version of ChatGPTNews The incident at CISA raises yet more concerns about the rise of ‘shadow AI’ and data protection risks

-

Laid off Intel engineer accused of stealing 18,000 files on the way out

Laid off Intel engineer accused of stealing 18,000 files on the way outNews Intel wants the files back, so it's filed a lawsuit claiming $250,000 in damages

-

PowerEdge - Cyber resilient infrastructure for a Zero Trust world

PowerEdge - Cyber resilient infrastructure for a Zero Trust worldWhitepaper Combat threats with an in-depth security stance focused on data security

-

Redefining modern enterprise storage for mission-critical workloads

Redefining modern enterprise storage for mission-critical workloadsWhitepaper Evolving technology to meet the mission-critical needs of the most demanding IT environments

-

The business value of storage solutions from Dell Technologies

The business value of storage solutions from Dell TechnologiesWhitepaper Streamline your IT infrastructure while meeting the demands of digital transformation

-

Cyber resiliency and end-user performance

Cyber resiliency and end-user performanceWhitepaper Reduce risk and deliver greater business success with cyber-resilience capabilities

-

Intel Alder Lake chips safe from novel exploits following source code leak, experts say

Intel Alder Lake chips safe from novel exploits following source code leak, experts sayNews The mystery surrounding how the code was leaked is a more interesting story, experts told IT Pro, despite others branding the incident "scary"

-

McAfee and Visa offer 50% off antivirus subscriptions for small businesses

McAfee and Visa offer 50% off antivirus subscriptions for small businessesNews UK Visa Classic Business card holders can access the deal starting today

-

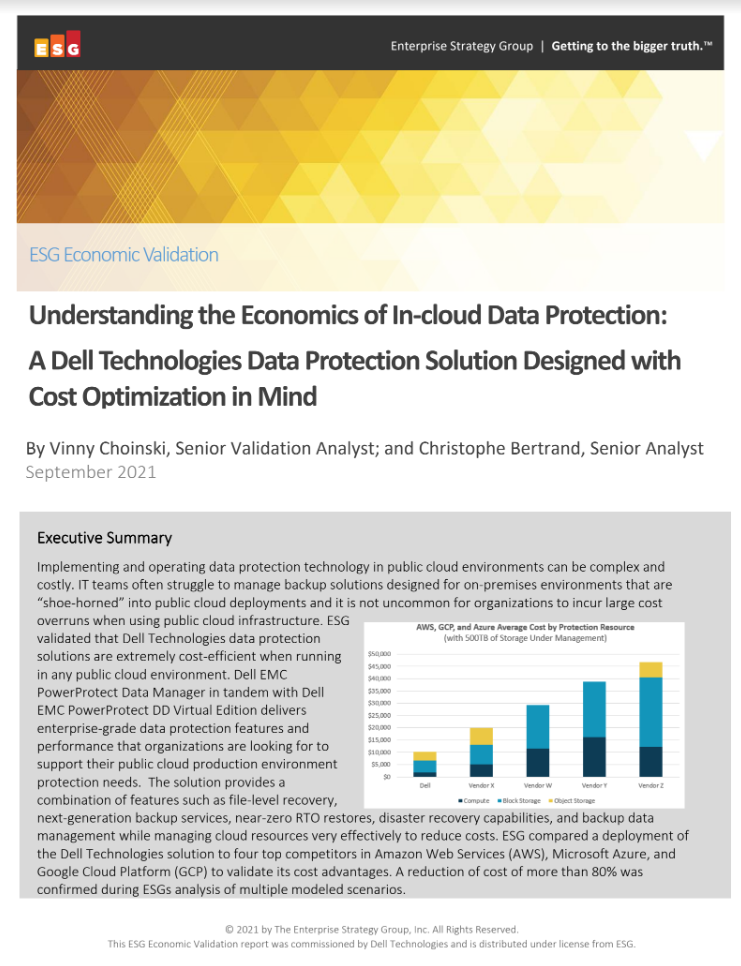

Understanding the economics of in-cloud data protection

Understanding the economics of in-cloud data protectionWhitepaper Data protection solutions designed with cost optimisation in mind