Google owns my soul and I don’t miss it one bit

The shift to remote working has made me realise that my head is now firmly in the clouds

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

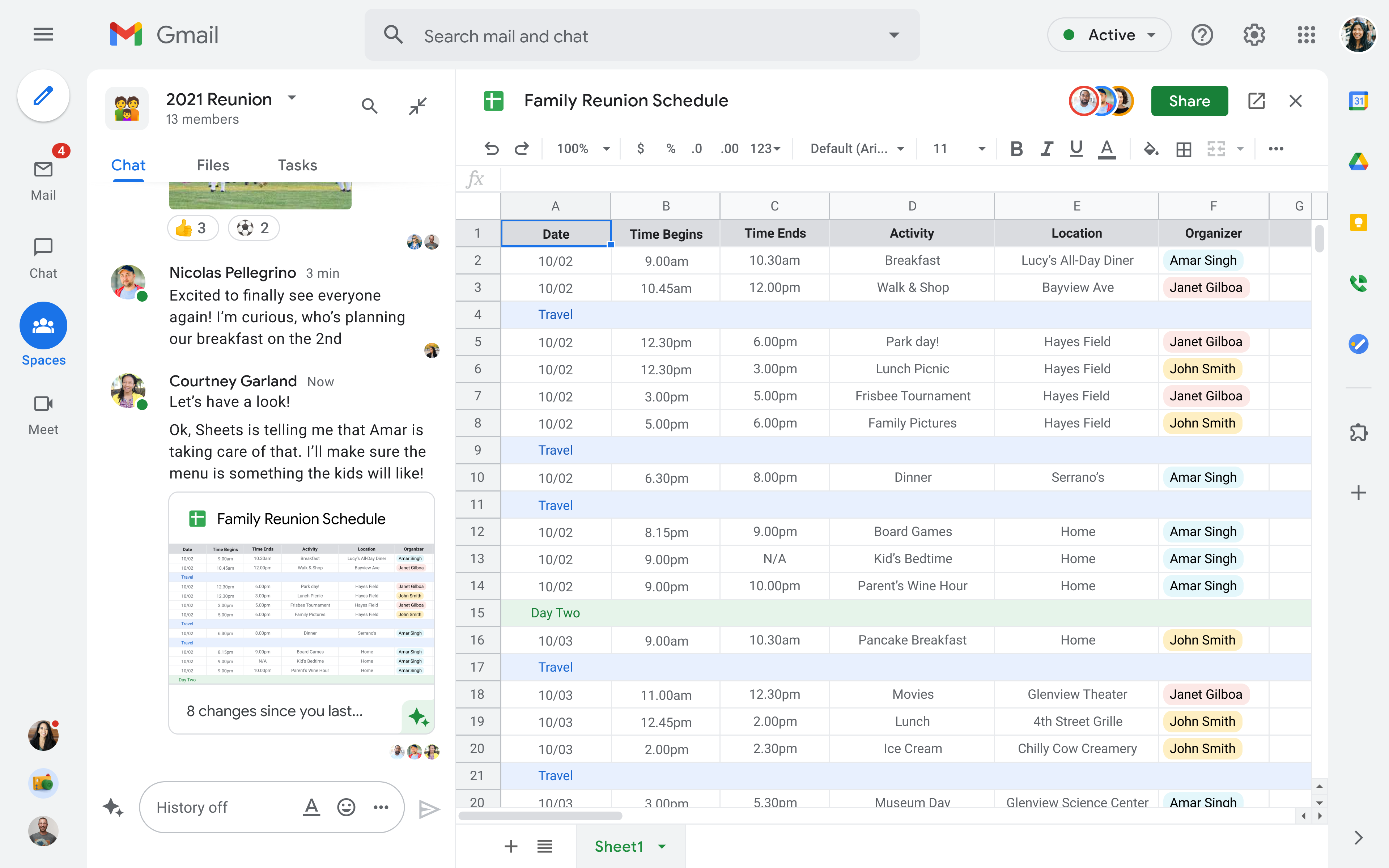

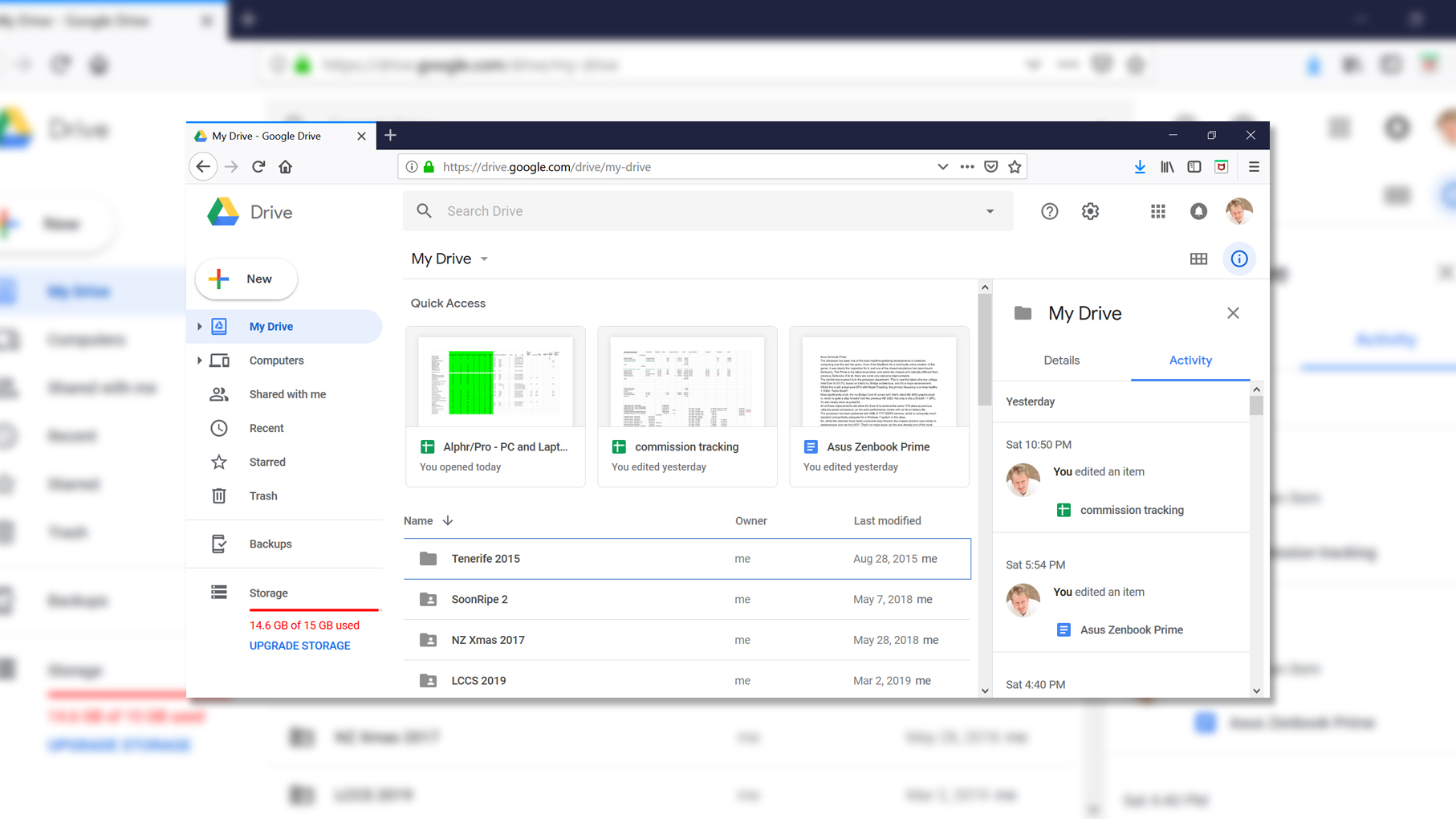

Two months ago, in PC Pro, I advised newly homeworking readers to “Get a Google account and a Chromebook”. This off-the-cuff suggestion made me realise how far I’ve drifted from the original personal computer revolution. That was about everyone having their own CPU and their own data, but I’ve since sold my soul to Google and I can’t say I miss it. When first turned on, my Asus Chromebook C301 sucked down all my personal data within five minutes, because I’d already placed it in Google Keep or Google Drive. I still have a Lenovo laptop but rarely use it, except via those same Google apps, and I don’t miss the excitement of Windows updates one bit.

My love for Google Keep is no secret and it only grows stronger as features such as flawless voice dictation and pen annotations get added. Previously I had spent over 30 years looking for a viable free-form database to hold all the research data – articles, pictures, diagrams, books, links – that my work makes me accumulate. The task proved beyond any of the database products I tried, with Idealist, AskSam and the Firefox add-on ScrapBook lasting longer than most. Those with long memories might remember how Microsoft promised to put the retrieval abilities I need right into Windows, via an object-oriented file system, but it eventually chickened out.

Keep’s combination of categories, labels, colour coding and free text search gives me the flexible retrieval system I’ve been seeking, but it still isn’t quite enough on its own: While it can hold pictures and clickable links, they’re not as convenient as actual web pages. For a couple of decades, I religiously bookmarked pages, until my bookmark tree structure became as unwieldy as my on-disk folders.

Nowadays, I just save pages to Pocket, which is by far the most useful gadget I have after Keep. A click on Pocket’s icon on the Chrome toolbar grabs a fully formatted page, complete with pictures and a button to go to the original if needed, making bookmarks redundant. I use the free version that supports tags similar to Keep’s labels, but the paid-for Premium edition has a raft of extra archival features for professional use. And, like Keep, it’s cross-platform so I can access my page library from Windows or a phone.

Does the cloud make stuff easier to find? To an extent, yes. Save too many pages to Pocket and, as with bookmarks, you’ve merely shifted the complexity rather than removing it. Sometimes I fail to save something that didn’t feel important at the time, then discover months later that it was, at which point Chrome’s history function comes in handy. I use it most to reopen recent tabs closed by mistake (I have an itchy trigger finger) but by going to myactivity.google.com I can review searches years into the past – if I can remember the keywords. Failing that, it’s plain Google Search or the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine, recently released as a Chrome extension.

My music nowadays comes entirely from Spotify. My own photos remain the main problem. I take thousands and store them both in the cloud and on a local hard disk, organised by camera (Sony A58, Minolta, Lumix), then location (park, Italy, Scotland). I’ve tried dedicated photo databases that organise by date, but find them of little help: place reminds me far more effectively than time. My best pictures still go onto Flickr, tagged thoroughly to exploit its rather superior search functions (it can even search by dominant colour). Pictures that I rate less Flickr-worthy I sometimes put on Facebook in themed albums, which also helps to find them. The technology does now exist to search by image-matching, but that’s mostly used by professionals who need to spot theft or plagiarism. I can only express what I’m looking for in words, such as “Pip fixing the Gardner diesel engine”.

What’s required is a deep-AI analysis tool that can facially identify humans from their mugshots in my contacts, recognise objects such as tables, chairs or engines, can OCR any text in a picture (such as “Gardner” embossed on a cylinder block), and then output its findings as searchable text tags. It wouldn’t surprise me if some Google lab is working on it. I realise that if Google went bust, or the internet closed down, I’d be stuck with local data again, but if things get that bad then foraging for rats to eat will probably be a higher priority.

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

So, while I still stand by my original answer recommendation to buy a Chromebook, my more thoughtful advice would now be this: keep your feet on the ground and your data in the cloud(s).

-

Google just added a new automated code review feature to Gemini CLI

Google just added a new automated code review feature to Gemini CLINews A new feature in the Gemini CLI extension looks to improve code quality through verification

-

Zyxel NWA50BE Pro review

Zyxel NWA50BE Pro reviewReviews The NWA50BE Pro offers a surprisingly good set of wireless features at a price that small businesses will find hard to resist

-

Microsoft looks to tempt legacy G Suite users with hefty discount

Microsoft looks to tempt legacy G Suite users with hefty discountNews The move comes after Google's decision to revoke free G Suite accounts created between 2006 and 2012

-

Google to shut down free G Suite accounts

Google to shut down free G Suite accountsNews Legacy G Suite users have been able to continue using their custom domain accounts for free for ten years

-

Challenging the rules of security

Challenging the rules of securityWhitepaper Protecting data and simplifying IT management with Chrome OS

-

Google Workspace is now available for everyone

Google Workspace is now available for everyoneNews The move means all of the tech giant's three billion users can access the full Google Workspace platform

-

Google Photos is free for just one more month

Google Photos is free for just one more monthNews "High-Quality" media and files will count toward a new 15GB free storage cap

-

The definitive guide to backup for G Suite

The definitive guide to backup for G SuiteWhitepapers How to find exactly what you need to keep your data safe

-

Google G Suite review: Suite like chocolate

Google G Suite review: Suite like chocolateReviews If you can make the leap to a cloud-centric usage model, G Suite provides seamless real-time document collaboration.

-

Head to Head: Google Apps vs Microsoft Office 365

Head to Head: Google Apps vs Microsoft Office 365Vs Mary Branscombe compares the enterprise versions of both and her conclusions may surprise you...