Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

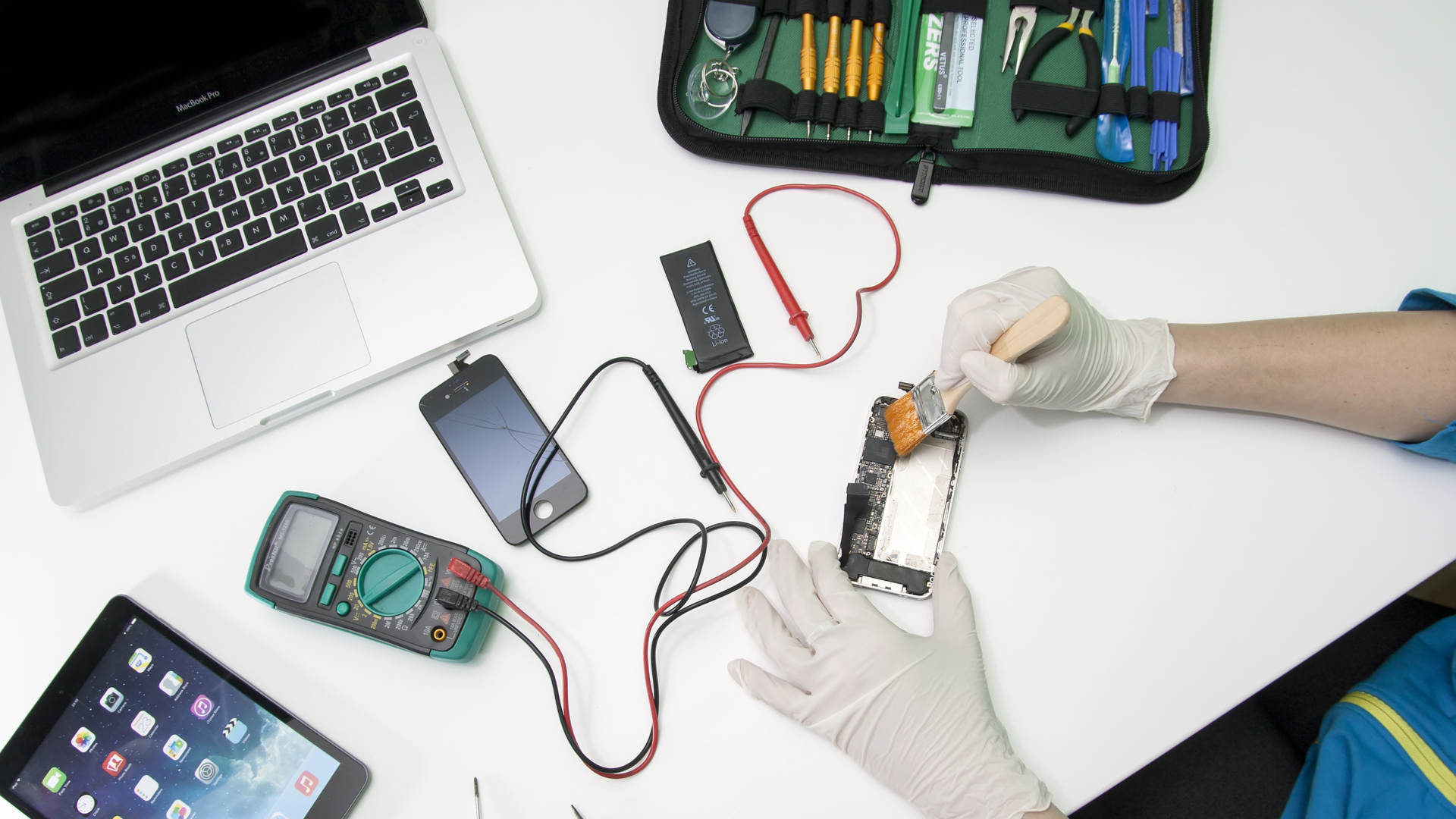

Your PC is emitting an unsettling burning odour; your smartphone screen has been smashed into a gazillion pieces. You need help and a Google search reveals your local area is teeming with repair “professionals”. How do you know which to trust?

If you need your boiler repaired, you might look for someone on the Gas Safe Register. If it’s an electrician you need, you might search the Registered Competent Person database. Other industries have established trust-marks which are instantly recognisable and give consumers that bit of extra confidence. But when it comes to fixing your computers or other gadgets, you’re largely on your own.

The repair ecosystem, and right to repair, is complex and messy, with technicians, safety experts, educators and consumer rights advocates generally agreeing we, as a nation, have lost our appetite to fix things. Legislators and manufacturers, too, clash over ways to make repairing more prevalent and sustainable. Because, meanwhile, literally anyone is at liberty to set up a business fixing hardware like smartphones and laptops, it’s vital that you don’t hand your kit to bad businesses; there are more than just a few pieces of advice to take on board when seeking out a technician you can trust.

A lost generation of repairers

It wasn’t so long ago that most high streets had a repair shop – a place that would fix household gadgets for a fraction of the price of a brand-new model. Sometime in the 1980s, society unconsciously embraced the linear economic model of ‘take, make, dispose’, and repair became unpopular and uneconomical. Professor Tim Cooper, an expert in product longevity from Nottingham Trent University explains: “Any small appliance is unlikely to get repaired because opening the item up costs money. If you’re buying a kettle for £20, nobody’s going to repair that”.

Now, we’re all waking up to why repair is a key part of environmental sustainability. Governments around the world are clamping down on manufacturers who have normalised unrepairable and disposable technologies because lobbyists and economists have successfully demonstrated that a repair-driven economy is feasible. A 2021 report from the Green Alliance estimates “the government could help to create over 450,000 jobs in the circular economy by 2035”, which is hugely encouraging, but because we lost our faith in repair, we lost the repairers.

We packed 1980s houses with rented technology. High street names such as Rumbelows and Radio Rentals leased tech as buying was often beyond the average family budget. As part of the rental agreement, breakages were fixed by a small army of professionals, skilled in the art of repair. “There was a postwar payday for most things,” says John Dunton, electronics engineer and writer. “Vast numbers of people were trained during the war; the Navy, Army and Air Force trained huge numbers of electrical technicians.”

Manufacturers also encouraged these technicians to repair even cutting-edge technology. The Amiga 500, one of the best-selling computers of all time, had electrical schematics inside its manual. Commodore designed it to be repairable by competent technicians and if these people hadn’t been trained by the military, they’d probably been through City & Guilds (C&G).

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

What about the C&G 6968 standard?

C&G 6968 covered the servicing of consumer electronics such as TVs, Hi-Fis and kitchen equipment. Dunton co-wrote some of the accompanying textbooks for the course. “City & Guilds were aimed at the people who worked for companies like rental operations,” he says. Although the public was largely oblivious to the City & Guilds certification, it gave credibility to the technician, so repair shops knew who to employ to maintain the reputation of their business.

C&G 6968 was discontinued around 2008. “Stuff gets much more integrated and reliability improves dramatically,” says Dunton. “Repaired by replacement comes in, then the cost of getting somebody qualified goes up, because you’re teaching less of them, so you are less interested in repairing stuff, because the cost of your repair is high. A vicious circle.”

RELATED RESOURCE

The COO's pocket guide to enterprise-wide intelligent automation

Automating more cross-enterprise and expert work for a better value stream for customers

Today, when we’re looking for someone trustworthy to repair technology, scrutinising a technician’s qualifications isn’t a primary concern, which is fortunate because they probably haven’t got any. C&G 6968 wasn’t replaced and electronics training is niche. Statistics from Eduqas, one of the largest providers of qualifications across England, show that only 1,044 candidates took GCSE Electronics in June 2021, falling to 672 for A-levels. There are around 800,000 GCSE pupils in the year group. Philip Glover, Eduqas’ Electronics Subject Officer explains: “In schools, electronics is competing against other subjects and [there is] difficulty in recruiting teachers with electronics expertise”.

This is a shame, as Glover explains it’s a great springboard for further study. “GCSE electronics provides a foundation for the study of electronics and engineering at either AS or A-level, an excellent start for students moving onto further education or apprenticeships.”

Further electrical education is more widespread for those wanting careers in industrial and domestic installations, but is lacking for devices such as tablets and games consoles. Thankfully, this is being addressed by providers such as The Electronics Group in Leeds, the UK’s largest independent electronics training centre, which is putting together a fault-finding course in response to the right-to-repair directive.

The YouTube finishing school

If we consider that most repairers receive no support from manufacturers in terms of schematics or spare parts, alongside a black hole in skills training, we need to acknowledge the part YouTube plays in ensuring anything gets repaired at all. Graham Lord of Adamant IT is a professional repairer. “I’m entirely self-taught and I think a lot of repair people are,” he says. “You don’t go to university to learn repair, you go to learn electronic engineering”.

Four years ago, he introduced a new service to his business, and his only training outlet was YouTube. “I got into board repair via Louis Rossmann’s [YouTube] channel. He put up a lot of material and was asking real questions about: How is this done? How do we do it? How do we get better at it?”

Aside from inspiration, the YouTube community has proved to be a powerful tool in dispelling the repair myths that manufacturers perpetuate. “You cannot fix a motherboard, they say, despite the overwhelming evidence on YouTube to the contrary,” says Lord. “They can say ‘we don’t recommend this’, but they cannot say ‘it cannot be done’”.

Ugo Vallauri, co-Founder and policy Lead of The Restart Project also believes online resources are important. “YouTube and other resources show attempts at filling the gap left by the lack of documentation made available by manufacturers,” he says. “[Manufacturers] could make the most comprehensive video about how to repair a certain product, but they don’t”.

In the absence of official training, YouTube is powering the current crop of repairers, but is it safe? Martyn Allen from Electrical Safety First works with government, manufacturers and retailers to improve safety standards. “In the space of the last two years, many qualifications have been delivered online and if it’s done well, it’s absolutely fine,” he says. “There are good ones, but there are some very bad ones and, when I mean bad, I mean dangerous”.

How to find repair trust-marks

In a marketplace crammed with self-trained technicians, how do you separate the diligent from the dangerous? There are many recognisable trust-marks which assess business practices. “Which? Trusted Traders recognise reputable traders who successfully pass an assessment carried out by our trading standards professionals,” says Lisa Barber, Which? computing editor. “When it comes to proving to the public you’re trustworthy, independent repairers should keep up to date with reviews given as well as ensuring that customer service is exceptional.”

Trust-marks allow a customer to expect that they’ll be treated well, but they don’t assess any technical capabilities, which lessens their value in the eyes of some independent repairers. Graham Lord has an interesting idea to enhance public confidence in trust-marks. “Provide a guarantee that if [a customer] has a bad experience, they will guarantee [the repair] up to a certain value. That provides worth to that check mark,” he claims.

Professor Tim Cooper believes there’s merit in introducing a technical-based trust-mark to boost consumer confidence. “When it comes to the repair economy, you’ve got products that we ought to be able to repair ourselves,” he says, adding there’s a “desire for an independent verified company, so I know that person hasn’t just woken up and thought ‘I’ll call myself a repairer and see how I get on’. I think there is a case for a scheme like that”.

Reviews allow us to make judgements about a business and their services, and even if some review platforms are fallible, there’s a truism that given enough time, good companies should be better reviewed than bad ones. Companies that publicly respond to their reviews, even the poor ones, show more of themselves to potential customers and transparency is critical for increasing consumer trust. “I think transparency is an important way to increase consumer’s confidence”, says Ugo Vallauri. “What’s really useful is for consumers to have the confidence that when they’re purchasing refurbished, if it’s not what they were thinking it would be, they can return it”.

Barber agrees. “Know your rights when buying second-hand. If you are buying from a retailer, you have far more protection than if you buy from a private seller, including being covered by the Consumer Rights Act, which dictates goods must be fit for purpose and of satisfactory quality”.

Ultimately, when looking for trustworthy operators, Vallauri believes the traditional pillar of exceptional aftercare will win the business. “There are some platforms where you might get the same warranty as a brand-new product and, to me, that gives excellent reassurance that a product is just fine”.

Bargaining for a fair repair

RELATED RESOURCE

The field guide to application modernisation

Moving forward with your enterprise application portfolio

Most tech repairers are trying to beat a system that’s stacked against both them and the consumer. Today’s gadgets weren’t intended to be repaired and many devices actively prevent it. As the public appetite for the right to repair grows, repairers need the manufacturers to change their mindset. “Manufacturers need to make products more repairable, more modular based,” argues Martyn Allen. “Some things are not able to be unplugged and replaced. That’s when you need the professional. It’s establishing the lines of what is possible by a normal person and what professionals need, and having clear information for the consumer.”

Repairers need access to documentation and spare parts, which is covered, for some device categories, by a piece of EU legislation known as the Ecodesign Directive. It contains a clause that Ugo Vallauri finds interesting. “It leaves an opportunity for each country to create a register of professional repairers eligible to access repair information and spare parts from manufacturers,” he points out.

Currently, no EU country has created a register of professional repairers and it’s unlikely we’ll see one in the UK as the government’s implementation of the same legislation is different. “That option [the register] is not included, which leaves it up to each manufacturer to decide whether someone has access to the repair information, spare parts and is considered a competent professional repair,” says Vallauri.

We’ve already explained that professional repairers often have nothing to prove their skills except a clutch of decent Google reviews, but some manufacturers are allowing independents to become ‘authorised repairers’. Apple’s Authorised Service Providers scheme allows some repair businesses to have access to certain tools and parts. Graham Lord looked at becoming an AASP and decided it wasn’t for him. “[AASPs] can buy the replacement motherboards directly from Apple,” he says. “They’ll charge the customer, say £700, but the customer will pay for it, because it’s ‘authorised repair’”.

One criticism is that certain manufacturer schemes dictate which parts must be replaced, instead of repairing the broken part. Paying £100 for a circuit-board fix is not an option presented to the customer because the scheme will only ‘authorise’ a more expensive circuit-board replacement. To be accepted into certain schemes, businesses are required to sign non-disclosure agreements (NDAs), which can be unappealing to independents like Lord. “Having to control people through NDAs, that’s just a blazing red flag. I don’t believe in hiding stuff”.

Zoe Avison from the Green Alliance is very clear on where we need to go to increase our trust in technicians: “Making it easier to repair electronics is good for the planet and good for people’s wallets,” she says. “Standards for professional repairers would give consumers confidence when choosing a repair service and help to reduce waste.”

Lee’s career began in TV as a programme maker for the BBC, ITV and Channel 4, specialising in education, history and science. He was part of the early video-on-demand team for ITV which lead to technical roles within the fledgling online-shopping department for ASDA/Walmart.

In 2003, he and his wife escaped the corporate world and setup a computer repair business focussing on the consumer side of the market.

Lee is a contributing editor and podcaster for sister title PC Pro with a particular interest in the right-to-repair movement and the circular economy. He can usually be found running around the streets of Yorkshire at a ridiculous time of the morning, and he’s also trying to solve a mystery involving David Bowie.

You can reach Lee at lee@inspirationcomputers.com or @tnargeel