Can the West bring chip production home?

As new chip fabs come online, the biggest names in tech remain reliant on Taiwan

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Having the majority of the world’s chip production in a single region or country brings risks. This was highlighted during the pandemic, when factory shut-downs and restricted movement across borders disrupted logistics, grinding global chip supply chains to a halt.

While the 2020-23 global chip shortage was a stark reminder of the global supply chain’s fragility, the reality is that pandemics are few and far between. However, when a single disruption can trickle down the value chain, distribution of manufacturing footprint is key to resilience.

This is especially the case “when the majority of the world’s most advanced chips are produced in a country where there are risks of natural disasters and a precarious political situation,” notes Jo De Boeck, chief strategy officer at research and innovation center imec, in reference to Taiwan.

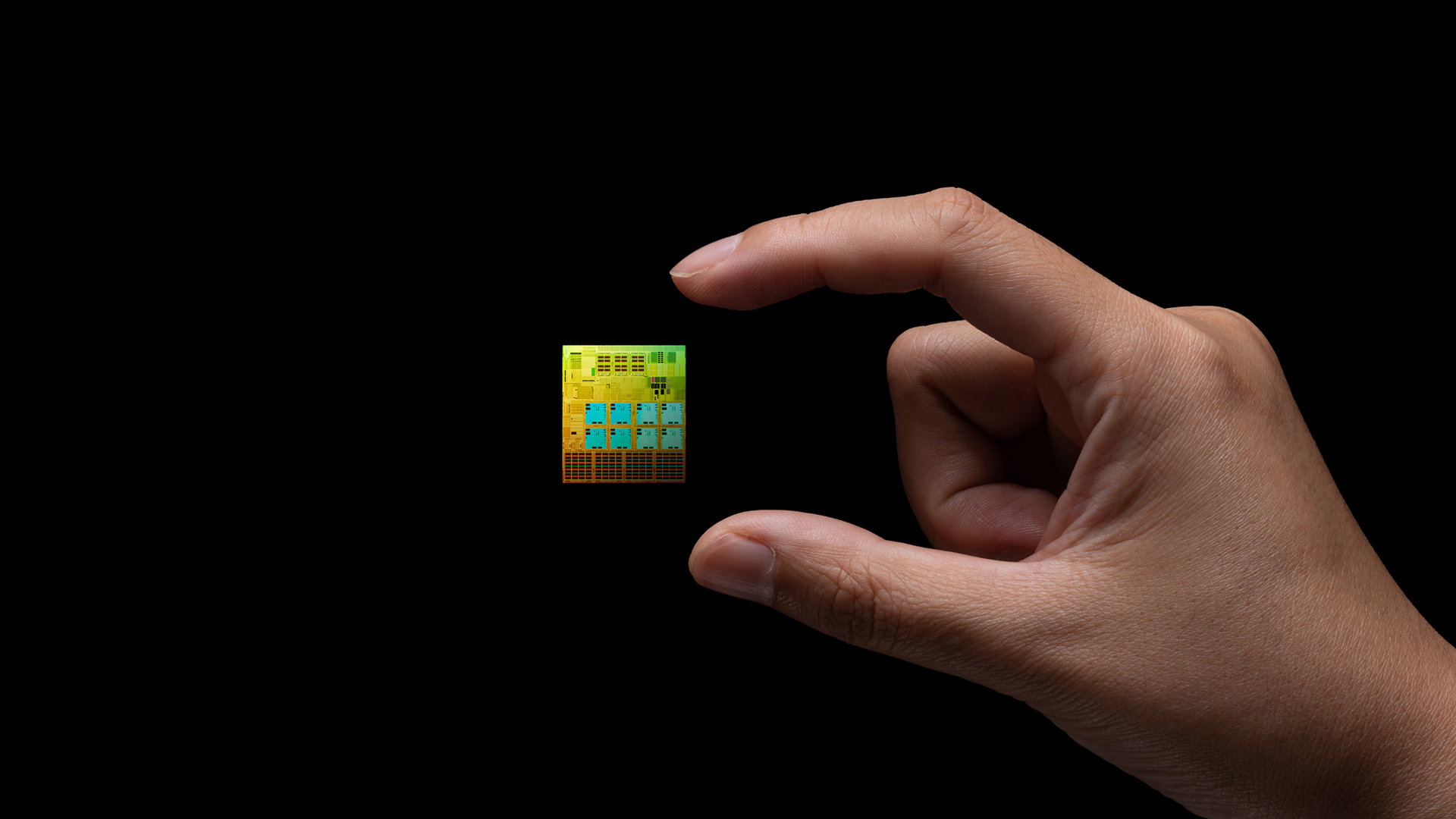

A staggering percentage of the world’s semiconductors are made in Taiwan, with Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) accounting for 70.2% of the global foundry market.

Taiwan’s semiconductor market is worth $35.55 billion and accounts for over 90% of the cutting-edge chips used for AI, per Mordor Intelligence.

The industry has acknowledged the need for more resilient semiconductor supply chains, with diversified production locations and greater capacity closer to where chips are used. But how much action has been taken to bring production back to the US and Europe?

Scaling up US chip making

Governments in both regions are investing in onshore chip production. Under President Biden, the US set aside $280bn through its CHIPS and Science Act, created to boost domestic semiconductor manufacturing. On the private sector side, projects include the expansion of Samsung’s US operations in Texas, while Intel – despite delaying or cancelling some new fabs, continues to invest in upgrades to its existing facilities.

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

Then there’s TSMC. After putting $65bn into the development of a 3nm fab in Pheonix, Arizona, it recently announced a further $100bn investment in US-based advanced semiconductor manufacturing. This will be used to build three new fabs, two advanced packaging facilities, and a major R&D center.

Companies planning to use TSMC’s Arizona fabs include AMD and Nvidia; the latter using the chip plants to build its Blackwell chips, which will be used to produce AI supercomputers and data centers entirely in the US for the first time.

These projects alleviate some of the concerns around a sole source supply, notes Nina Turner, IDC’s research director for edge AI processor architecture. But she adds US volumes will be small compared with Asia, and that TSMC’s investments aren’t immediately bringing the latest technology to the US. “While TSMC will bring it to the US eventually, the latest technology still resides in Taiwan.”

Europe’s progress

Over in Europe, there’s limited advanced node fab build out, Turner continues. “The companies who’ve established fabs are addressing other markets like automotive and industrial, and adding capacity at the non-bleeding edge.”

Similar to the US legislation, the EU proposed its own Chips Act to support a resilient semiconductor ecosystem. This has included strategic initiatives like the NanoIC pilot line – a flagship platform for advancing beyond-2nm system-on-chip technologies, bridging the gap between cutting-edge research and industrial adoption, says De Boeck.

Also under the EU Chips Act, the European Commission (EC) has granted Integrated Production Facility (IPF) or Open EU Foundry (OEF) status to four semiconductor projects.

IPFs are vertically integrated semiconductor manufacturing facilities that combine several stages – from design and manufacturing to testing and packaging, while OEFs are facilities that dedicate at least part of their capacity to producing chips for external customers. These statuses give the projects priority administrative support, streamlined permit processes and advanced access to pilot lines.

Projects granted IPF status are:

- Ams-ORAM’s integrated facility in Austria to manufacture 180nm mixed signal and automotive-grade qualified technologies.

- Infineon Technologies’ Dresden facility for the manufacture of analog and mixed-signal integrated circuits.

- STMicroelectronics’ Italian facility to offer vertical integration of the entire 8” silicon carbide (SiC) value chain production processes – something not yet present in the EU.

The single OEF is ESMC, a joint venture (JV) between TSMC, Bosch, Infineon, and NXP, which will produce high-performance, energy-efficient chips using advanced FinFET technology on 300mm wafers in Germany.

Europe’s 20% reality check

In its Chips Act, the EU set a goal of reaching 20% of global chip output by 2030; however, even with the support currently in place, experts agree this isn’t feasible

“Europe has minimal progress to show. It has niche areas of expertise: WFE – Advanced Semiconductor Materials Lithography (ASML), analog/discrete – NXP Semiconductors, Infineon and STMicroelectronics (STM), and research – imec, but things haven’t really changed for years,” says Gaurav Gupta, VP analyst at Gartner. “The only exception is the new JV fab.”

“I think even the EU now realizes that it can’t get to 20%. It’s currently at the 7-8% range, and even if it can maintain that by 2030 that would be a success.”

Obstacles to overcome

Both Europe and the US face commercial and operational obstacles regarding scale up, the largest being costs.

Turner reports that costs to manufacture chips in the West will remain more expensive (possibly more than 20% in the US) than Taiwanese equivalents. Hyperscalers are probably more willing to pay the price increase, she says, for insurance against geopolitical issues, reduced export-control complexity and lower logistical risk for multibillion-dollar AI clusters. However, she believes that higher volume consumer device manufacturers, such as Apple and Qualcomm, are less likely to commit to the extra expense.

Regulations will also play a factor in keeping costs up and slowing projects down, adds Gupta, pointing to more restrictive labor agreements as well as a skills shortage.

Clearly a lot still needs to be done for the West to be able to compete against Asia, including government subsidies, experts agree. Gupta says these will be needed to attract more private sector investment, as chip manufacturing is capital intensive, with ROI taking time.

A slow shift westward

While we will see some diversification of chip production over the next ten years, manufacturing will still largely center around Taiwan and Asia more generally. This is because a number of western projects have been delayed, and building a fab takes time.

Analysts agree the US may gain a few percentage points in terms of semiconductor manufacturing while Europe is likely to maintain, rather than grow, its share. The challenge, says Turner, is that while the US and Europe invest, so do the other regions. South Korea is investing $470bn over 20 years to build a semiconductor cluster with Samsung and SK Hynix for example, while Japan has pledged over ¥1 trillion to support its domestic chip industry.

The West’s efforts won’t eliminate supply chain risks overnight, but every investment, capability upgrade and policy push represents a step towards a more balanced global landscape. Progress may be gradual and uneven, but these moves collectively help shore up the resilience of the semiconductor ecosystem, reducing the vulnerability that comes from relying so heavily on a single region.

Keri Allan is a freelancer with 20 years of experience writing about technology and has written for publications including the Guardian, the Sunday Times, CIO, E&T and Arabian Computer News. She specialises in areas including the cloud, IoT, AI, machine learning and digital transformation.