What's powering Britain’s fibre broadband boom?

Expansion in full-fibre infrastructure and many new providers are making it stupidly cheap to get ultrafast internet connections in all corners of the UK, although the boom might not last

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

From The Highlands of Scotland to the villages of Cornwall, Britain is in the midst of a full-fibre frenzy, with dozens of smaller providers – so-called altnets – running fibre to the doors. It’s a massive land grab and, with companies keen to please investors, they’re offering stupidly fast broadband at stupidly cheap prices to attract customers.

But can it last? Will these cut-price fibre providers be able to compete with giants such as Openreach and Virgin Media over the long term? Or will the market go the same way as it did with ADSL, with smaller fish swallowed by the bigger sharks?

What's triggered the full-fibre explosion?

When it comes to delivering end-to-end fibre connections, Britain had – until relatively recently – been lumbering along at a pedestrian rate. At the start of the 2010s, BT set an ambitious target to reach 25% of British households with full fibre, but it quickly faltered. Openreach largely concentrated on delivering the much slower and cheaper fibre-to-the-cabinet (FTTC) and full fibre remained a rarity.

In the past few years, however, something changed. Although Boris Johnson’s bluster about delivering ultrafast broadband to everyone was typically exaggerated, there has been a serious surge in Britain’s full-fibre rollout and experts do give credit to the government and regulator Ofcom for giving it a shove.

“The number of alternative full-fibre networks in the market has rocketed to over a hundred in just the past three to four years, and this stems from the combined impact of several changes,” says Mark Jackson, editor-in-chief of ISPreview.

“Some examples of positive changes include demand side-interventions, such as the government’s rural gigabit voucher scheme, making the economic model for rural builds more viable, and support for providing fibre to public-sector sites, which can later be harnessed by commercial networks for further expansion. Ofcom has also made it easier and cheaper for altnets to viably run their own fibre over existing telecoms poles and underground cable ducts on Openreach’s infrastructure.”

Lit Fibre is an altnets that’s benefited from access to Openreach’s ducts and poles. The company’s CEO, Tom Williams, says the long battle to get physical infrastructure access (PIA) to Openreach’s infrastructure was crucial. “I was involved in PIA right from the very beginning and… it took a good three to five years to get that product to a place where it was viable enough for people to overcome the challenges that it faced,” he says. “I think some of the bigger companies are still struggling with some of those challenges, which is a perfect set of circumstances for more entrepreneurial companies to spring up and take advantage.”

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

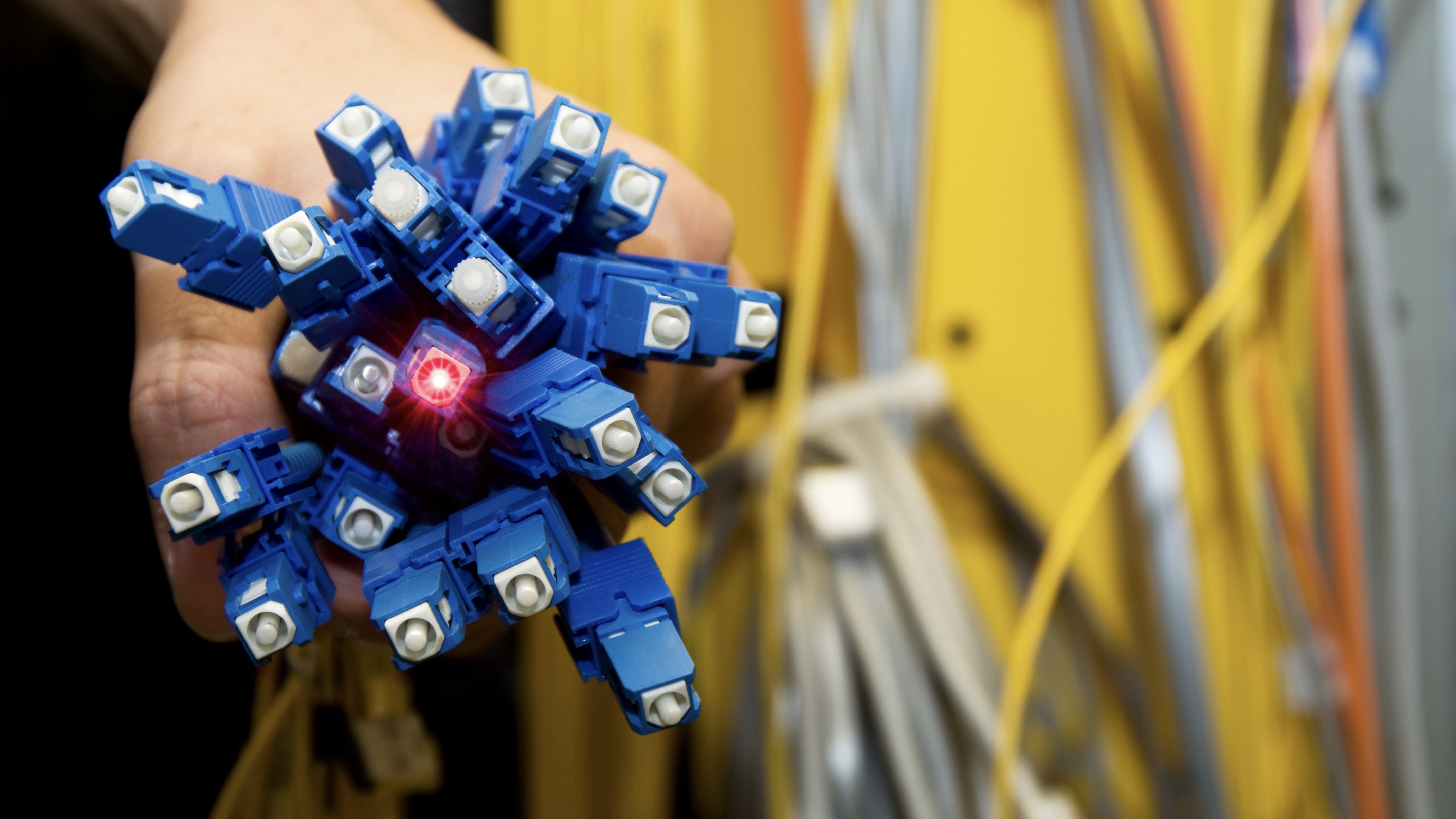

Breakthroughs in PIA have allowed alternative providers to enter the market

The other big factor is money – and plenty of it. With the ongoing economic uncertainty, there’s an appetite to invest in solid infrastructure projects, especially infrastructure that’s going to last a long time. The fibre being put into the ground now will last for at least a generation to come, because as Stewart Crabb, director of B2B at GoFibre says, “nothing travels faster than light”.

GoFibre, which is installing fibre in some of Scotland’s more rural areas, is installing XGS-PON and 25G PON technology from Nokia in its network to future-proof for the speeds that might be needed in the 2050s or 60s. “We’re not building it for today, we’re looking far into the future of what people will need, because theoretically that can deliver 10Gbits/sec to a home,” says Crabb. “Ten gig will never be used in a home today, but we don’t know what’s going to come 20, 30 or 40 years down the line.”

Why altnets have an advantage

The emergence of 100-plus fibre providers is inevitably going to splinter the broadband market, meaning each of those providers will be counting customer numbers in the tens or hundreds of thousands, rather than the millions or tens of millions of people on Virgin Media or Openreach lines. So how do smaller operators hope to compete with the industry giants?

One man who should know is Steve Robertson. He used to be the CEO of Openreach, but has recently joined Lit Fibre as a non-executive director. He believes the biggest advantage the altnets have is they are “starting a business with a clean sheet of paper”.

“The infrastructure space offers you the opportunity to do things that you just can’t do if you’ve got a massive legacy, as I know only too well,” he says. “Don’t get me wrong – there are great things about having a legacy… it’s not a dirty word. But having a clean sheet of paper does give you certain opportunities.

RELATED RESOURCE

Leverage automated APM to accelerate CI/CD and boost application performance

Constant change to meet fast-evolving application functionality

“If you are a smart, well-funded, intelligent, alternative network provider, you’ve got the opportunity to build and operate your network in a way that is quite different from a big legacy operator,” Robertson adds. “And in doing that, you can give customers a different sort of experience, you can be more personalised, you can be more agile. There’s a big market and there’s places for lots of different flavours.”

Being a new provider also allows companies such as Lit Fibre to shake off some of the problems that have long afflicted the broadband business. “If you look at things like TrustPilot, people are very suspicious, disillusioned and mistrustful of the industry,” says Williams. “Right back to the mid-2000s, people have been saying ‘I don’t get what I pay for’ because it’s always been ‘up to’. So there’s a big job for companies like us to educate the consumer as to how different it is. It’s about building that credibility and demonstrating the fact that full fibre is completely different.”

The other advantage is cost. By piggybacking on Openreach infrastructure and not bearing the cost of digging up roads, the altnets can be very competitive on price. With so many altnets in the landgrab phase, they’re driving down prices to attract customers. “You have got some [altnets] that are coming in and trying to bump up their customer base as quickly as possible, coming in with competitive pricing,” says GoFibre’s Stewart Crabb. “For the end user, that’s great. You are getting more than what you’re getting today for, if not a better price, the same price [as your current broadband].”

The influx of low-cost full-fibre providers is also putting pressure on the big players to not only accelerate the rollout of their own full-fibre networks, but to keep prices down. Openreach doesn’t sell directly to consumers; it wholesales its network to ISPs such as Sky, TalkTalk and Zen Internet. But the company’s managing director for fibre and network delivery, Matt Hemmings, admits the altnets are keeping Openreach on its toes. “I think that [competition] is a very positive thing for UK PLC and its customers, and we are making sure that we remain very competitive on [wholesale] price to ensure that we continue to grow and scale our business, and generate the returns that we that we want to make on our business case for our investment in FTTP,” he says. “The UK is building more fibre homes today than it ever has before and the pace of build accelerates every single quarter.”

Those cheap fibre prices might not be an introductory flash in the pan, either. “If we look across other markets where FTTP has matured, then if anything gigabit speed packages actually become even cheaper. Put another way, over the longer term, there’s scope for prices to fall further and for speeds to increase. Some ISPs are already charging around £25 to £35 per month for their top 1Gbit/sec package, and that may become much more common over the next five years.”

How long can Britain’s broadband boom last?

The full fibre expansion comes alongside a shift in the way these services are sold. For years, broadband has been bundled with other products, such as television, landline and mobile phone packages. But the bundles are beginning to unravel. “We are seeing the market shifting,” says Hemmings. “I couldn’t tell you my landline number, I don’t remember the last time I used my landline. I think and we will continue to see that market shift but we have an obligation at Openreach to ensure that we consider all customers and all their needs across the entire spectrum.”

Openreach’s ongoing drive to switch off the old PSTN network will drive a further stake through the heart of the landline business, with most consumers either sticking to their mobiles or relying on VoIP services for phone calls.

While customers might reap the benefits of cheap gigabit fibre connections for a few years to come, there are doubts over how long the British broadband boom can last. Indeed, in the early days of the cable rollout, there were numerous regional providers that eventually consolidated into one or two big players. When dial-up and ADSL first took off, there were hundreds of smaller ISPs, which were one-by-one subsumed by the bigger companies.

Almost everyone in the industry – even the altnets themselves – concede that there will be similar consolidation in years to come. “It will happen,” says GoFibre’s Stewart Crabb, “but the networks need to be built before you can go buy it. The important thing is getting those networks in the ground and getting customers on it, and getting everybody using it, then you’ll start to see acquisitions.”

North Berwick, a seaside town in Scotland, is one of the locations GoFibre has reached with its fibre rollout

RELATED RESOURCE

Why you need process mining in your RPA strategy

Reducing workloads so more time is spent on strategic thinking

We’re already starting to see overbuilding – areas with two, three or more full-fibre providers – and that creates problems for the business case. “We have a business case to build 25 million homes, which is about 80% of the UK, and we probably wouldn’t stop there,” says Hemmings. If you add up all of the announced plans to build from the various providers, it comes to 75 million homes. This is a problem when there are only 27 million homes in the UK. “I don’t think that, personally, is a sustainable market position,” he says. “I think you will naturally see consolidation over time.”

The good news is that strong competition is forcing altnets to build in places with less competition, places that might not otherwise have got fibre. GoFibre is targeting more rural areas in Scotland and the North of England, for example; Lit Fibre has rolled out in less affluent locations such as Clacton in Essex, because customers can afford its competitive prices and it delivers benefits to the entire community.

It’s the more competitive, inner-city areas where the crunch is likely to be felt. “The market reality is that having a mass of smaller players, many of which will be competing over some of the same areas, often overbuilding several other opponents, is not sustainable,” says ISPreview’s Mark Jackson. Even in dense urban areas, with plenty of customers in small geographic areas, you’d still run into problems with more than five networks competing.

“Wide-scale consolidation in a market that has become as aggressive competitive as this one is thus inevitable,” he continues. “I suspect, given enough time, that we’ll end up back in a position with a handful of large infrastructure players, followed by a smattering of medium-sized and smaller players in particular or niche areas. But not the 100-plus altnets you see today.”

Barry Collins is an experienced IT journalist who specialises in Windows, Mac, broadband and more. He's a former editor of PC Pro magazine, and has contributed to many national newspapers, magazines and websites in a career that has spanned over 20 years. You may have seen Barry as a tech pundit on television and radio, including BBC Newsnight, the Chris Evans Show and ITN News at Ten.

-

Tomorrow's fraud techniques

Tomorrow's fraud techniquesITPro Podcast Leaders need to proactive as attackers launch more consistent, sophisticated attacks

-

Met Office hails huge efficiency gains in first year of cloud supercomputing with Microsoft Azure

Met Office hails huge efficiency gains in first year of cloud supercomputing with Microsoft AzureNews In moving to the cloud, the Met Office has bolstered operational resilience and helped to deliver more accurate forecasts

-

Sovereign infrastructure spend to triple in Europe as fifth of workloads stay local

Sovereign infrastructure spend to triple in Europe as fifth of workloads stay localNews Gartner says global spending on sovereign cloud infrastructure will climb 35% over the next year

-

Majority of English data centers use less water than a 'typical leisure center' as operators embrace new cooling methods

Majority of English data centers use less water than a 'typical leisure center' as operators embrace new cooling methodsNews England’s data centers are surprisingly efficient when it comes to water consumption

-

‘Too many organizations assume they’re more resilient than they actually are’ – UK firms are facing huge financial losses from IT outages and downtime

‘Too many organizations assume they’re more resilient than they actually are’ – UK firms are facing huge financial losses from IT outages and downtimeNews Many organizations are failing to put in place contingencies for IT outages and downtime, research shows

-

Meta is working on a 5GW data center to supercharge AI infrastructure – and Mark Zuckerberg says one cluster alone ‘covers a significant part of the footprint of Manhattan’

Meta is working on a 5GW data center to supercharge AI infrastructure – and Mark Zuckerberg says one cluster alone ‘covers a significant part of the footprint of Manhattan’News Mark Zuckerberg detailed plans for a huge infrastructure investment program in a post on Threads earlier this week – here's what you need to know.

-

So much for data sovereignty — AI infrastructure is dominated by just a handful of countries

So much for data sovereignty — AI infrastructure is dominated by just a handful of countriesNews Oxford researchers suggest AI infrastructure will decide a nation's global impact in the future, just as oil production has over the last few decades.

-

‘This is the largest AI ecosystem in the world without its own infrastructure’: Jensen Huang thinks the UK has immense AI potential – but it still has a lot of work to do

‘This is the largest AI ecosystem in the world without its own infrastructure’: Jensen Huang thinks the UK has immense AI potential – but it still has a lot of work to doNews The Nvidia chief exec described the UK as a “fantastic place for VCs to invest” but stressed hardware has to expand to reap the benefits

-

Google shakes off tariff concerns to push on with $75 billion AI spending plans – but analysts warn rising infrastructure costs will send cloud prices sky high

Google shakes off tariff concerns to push on with $75 billion AI spending plans – but analysts warn rising infrastructure costs will send cloud prices sky highNews Google CEO Sundar Pichai has confirmed the company will still spend $75 billion on building out data centers despite economic concerns in the wake of US tariffs.

-

Cisco wants to capitalize on the ‘DeepSeek effect’

Cisco wants to capitalize on the ‘DeepSeek effect’News DeepSeek has had a seismic impact, and Cisco thinks it has strengths to help businesses transition to AI-native infrastructure