Why video conferencing is so tiring and what you can do about it

You’re not alone if you find video meetings far more tiring than the real thing

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

“After a week of shelter-in-place, I was just flabbergasted by how intense and exhausting it was,” wrote Jeremy Bailenson, a Stanford University professor, in a piece by Microsoft Research that examined why people found online meetings so much more tiring than the real thing.

On the surface, this doesn’t make sense. In important meetings, we need to be on top form: we need to judge how, when and with whom to interact; think on our feet; and simply be alive to all the messages, verbal and physical, being transmitted. The adrenaline that carries us through such meetings quickly dissipates once they end, leaving us drained.

You’d think that online meetings would be more relaxed affairs. You’d be wrong. “It is a lot more tiring,” says professor Paul Lee, co-director of research at the United Lincolnshire Hospitals NHS Trust, who along with the rest of his profession has switched to online meetings and consultations. “Previously, we could sneak out for a coffee; nowadays, meetings are back to back. There’s no opportunity for socialisation and our downtime is greatly reduced.”

Nor are these the only factors. The Microsoft study corroborated that remote collaboration is more mentally challenging than in person, with the brainwave patterns associated with stress and overwork much higher. Another Microsoft study confirmed that the high levels of sustained concentration needed lead to fatigue after about 30 to 40 minutes of meetings. In a day filled with such video calls, stress is measurable about two hours into the day. This begs one question: why?

Missing your cue

The visual cortex is the largest system in the human brain. We respond to and process visual data better than any other type of data: The human brain processes images 60,000 times faster than text, and 90% of information transmitted to the brain is visual. Recent research found we can extract meaning from images in under 20 milliseconds, which is down at the refresh rate of a decent monitor.

We’re great at visual processing, yet seeing people onscreen is unnatural. Our poor, overtaxed brains must process differing backgrounds from person to person, deal with oddly sized heads (randomly big and small depending on camera and distance) and with differing image quality.

Then there’s a subtle and disturbing set of problems associated with latency, overlap and out-of-sequence responses to stimuli. The delay in feedback to each other, even though it can be measured in tens of milliseconds, plays havoc with our learned social interactions. There are all kinds of subtle cues – head nods, facial twitches, body language – we use to show that we want to speak, or that we agree or disagree. It’s like being in a room full of socially inept colleagues who don’t know when to shut up or interject.

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

Professor Lee adds another reason why we struggle in big online meetings: “Group calls require the same level of attention as a one to one and it’s much harder for a colleague or the chair to ‘bail you out’ if you lose your flow.”

A window to the soul

Scientists began studying problems with eye contact – known as “gaze misalignment” – in the 1960s. It’s an issue that’s endemic in video calls: We look at people on screen, but the webcam that people see us through is mounted above the screen, which usually means at forehead height if you’re using a desktop monitor, while on a laptop you often end up talking to chins and nostrils. It might only be a few centimetres, but humans are remarkable at social interaction and our conditioned brains tell us that our colleagues are not paying attention as their eyes seem elsewhere.

Similarly, our brains are aware of others based on their locations. In video calls, it’s harder for the brain to notice eye contact irregularities.

Personal space

Size matters! Camera type, desk and seating position, plus the unnatural effects of wide-angle lenses (which accentuate depth effects), not only lead to differences in the perceived size of people but can also trigger “personal space” responses. A head that appears large in your field of vision is associated with someone being up close, decidedly within your personal space. Millions of years of evolution have taught our reptilian brains that when things are that close, it’s either a threat or something a little more romantic.

Then there’s sound. Our auditory cortex is highly developed, which is why differences in audio clarity and perceived volume place a further strain on us during meetings. Visual challenges might be exhausting, but audio issues are even more disruptive: we seem better at ignoring poor visual quality than bad audio. When there are large volume differences between attendees, the process becomes taxing and uncomfortable. Meanwhile, the effects of hearing your own speech as an echo (delayed auditory feedback) is so profound that it’s been weaponised.

So we should abandon video meetings, right? Having experienced many decades of early mornings, long car, train and plane journeys and late nights, I can say with some confidence that video meetings are mostly better than the alternatives, despite all this.

Rather than return to face-to-face meetings as the default, we need to actively tackle the problems.

Fighting back

The common experience in video calls puts participants in their personal little box, tiled across your screen. But the discontinuity of everyone in a call having different backgrounds fragments this view, making it harder to pick people out.

A technique I’ve tried in my business, and with some success in Teams and Zoom thanks to their support for virtual backgrounds, is to have attendees use the same, simple background. A plain white room works well. We also took photos of our office and used those. It certainly felt more joined up, more like we were in a shared space rather than an eclectic collection of different rooms.

I’m not a huge fan of the “switch to active speaker” feature in most video calling solutions. In real life, I rarely see people teleport into my field of view. Film directors love this kind of cut because it creates tension and pace – I remain to be convinced that it makes for a good meeting experience. I prefer to pin the people I want to watch, either because they’re the main speaker or because I want to pay attention to their body language.

Some collaboration tools are trying to take things further. Microsoft is introducing Together mode, which places all participants in a virtual room, lecture theatre and the like. It shows promise, but it urgently needs to normalise how large everyone appears. Still, it’s a less expensive investment than the specialised cameras and screens that the likes of Cisco would love you to buy.

Handling issues of latency is harder. These inevitable delays mean people inadvertently talk over each other or miss their cue to interject. It’s not their fault. The ping time between, for instance, London and Lisbon is 50 milliseconds – well within our visual cortex’s ability to detect. Calls to Los Angeles see that rise to almost 130ms and Melbourne is a full quarter-second. Double that for round-trip time.

And this delay can’t be solved by technology alone: almost 40% of the Melbourne delay is the time light takes to travel the distance (56ms for 16,900km).

For this problem, we may need to learn new etiquette. Staying on mute until ready to talk, politely raising a digital or actual hand when you have something to say; adding questions via chat for a moderator to coordinate. In parallel, we may need to be a lot more overt with our normally subtle cues, so that attendees have to work less hard at “reading the room”.

Fix with a gaze

Solving gaze misalignment is going to be trickier. The first bit is easy enough: getting the camera at eye level should be on everyone’s list. Using a laptop is no excuse as we’ve known for many years that they should be hooked up to a proper mouse and keyboard with the screen elevated to face height; it’s standard display screen equipment health and safety stuff (which most people seem happy to ignore). But you inevitably look at the faces on the screen, not the camera lens, so appear to be looking at everyone’s hair or whatever is behind them.

We’re yet to see laptop displays where a webcam peeps through the middle of the screen, so a smarter approach is to digitally correct the apparent viewpoint of each person. Until this becomes mainstream, the best we can do is to minimise gaze misalignment through our setup.

We can solve image quality. This is a simple matter of using decent webcams backed by good lighting. You also need to make sure there’s enough bandwidth for the greater upstream demands.

Until tools like Together mode can correct for size, ask people to adjust their camera zoom or reposition the camera distance. You should be aiming for head, shoulders and chest.

Weaponised audio

As with the webcam, the microphone and speakers or headphones should be reasonable quality. Those things that come with your smartphone aren’t going to cut it in most cases. Decent, noise-reducing headphones are a good start, but people wearing headphones in meetings is a bit weird and rarely comfortable for the hours they’re needed these days. I’ve mostly switched to a reasonable quality desk mic and inexpensive PC speakers. If you’re in a private space, experience shows this to be more comfortable and less taxing than the “voices in my head” experience of headphones. Plus, it’s oddly uncomfortable to talk to someone wearing headphones.

It’s vital that everyone works to get their audio levels equalised so that people neither whisper, nor shout.

Equally critical is ensuring that there’s no echo or feedback. The former can happen if you aren’t using headphones so turn the speakers or the microphone sensitivity down. If you’re using headphones, it probably means there’s someone else in the same meeting within earshot. The same is true of feedback. Get noise-cancelling headphones, move to another room or turn everything down. It’s impossible to talk while hearing your own voice as an echo.

It’s also important to eliminate background noise, whether it’s the clunking of the dishwasher or kids’ chatter. In my case, the occasional use of the laser printer is horrendously intrusive. For this, I’ve been using the rather impressive Krisp technology. It’s not perfect, but it helps much of the time.

Two final points about video, which may at first seem contradictory. First, attendees should have their video on if speaking. We get a chunk of the meaning of what’s being said from what we see – leaving video off is increasingly considered to be rude.

Second, consider dumping video altogether if it doesn’t add anything meaningful. “I personally don’t think video consulting is here to stay,” says professor Lee. “We are switching back to phone consultations with patients.” What is lost by switching from video to phone? “Nothing! Patients don’t want to use it and often don’t have the right equipment. Telephone is easier.”

Exhaustion

Early in the pandemic, I was hitting six hours of contiguous meetings on some days. If I were to look back at my Fitbit sleep patterns for those days, I suspect I’d see the impact.

In the real world, we mostly walk between meetings, so get some chance to stretch our legs. Those breaks are important and there’s a handy solution if you book your meetings via Outlook using the “End appointments and meetings early” option (File | Options | Calendar). See the screenshot on the left for my recommended settings.

This brings me to my final recommendation: actively booking focus time. Some teams at Microsoft have “no meeting Fridays”, while Cloud2, the company I founded, has just mandated no meetings before 10am. As we adopt a more connected yet more remote lifestyle, we need to actively guard against any negative effects that may arise. Businesses need to maintain the productivity of their staff. People need to protect the quality of their personal time.

-

Pulsant unveils high-density data center in Milton Keynes

Pulsant unveils high-density data center in Milton KeynesNews The company is touting ultra-low latency, international connectivity, and UK sovereign compute power to tempt customers out of London

-

Anthropic Labs chief claims 'Claude is now writing Claude'

Anthropic Labs chief claims 'Claude is now writing Claude'News Internal teams at Anthropic are supercharging production and shoring up code security with Claude, claims executive

-

Infostretch and INDIASHIELD partner to resolve COVID crisis in India

Infostretch and INDIASHIELD partner to resolve COVID crisis in IndiaNews Infostrech’s support platform aids INDIASHIELD’s emergency healthcare

-

A new age of asset management

A new age of asset managementIn-depth Can migrating a business’ Active Directory to the cloud become a core resource as the consumerisation of tech continues?

-

VaxAtlas' looks to connect the public to COVID-19 vaccine distributors

VaxAtlas' looks to connect the public to COVID-19 vaccine distributorsNews New platform unveils portable approach to COVID-19 vaccine distribution

-

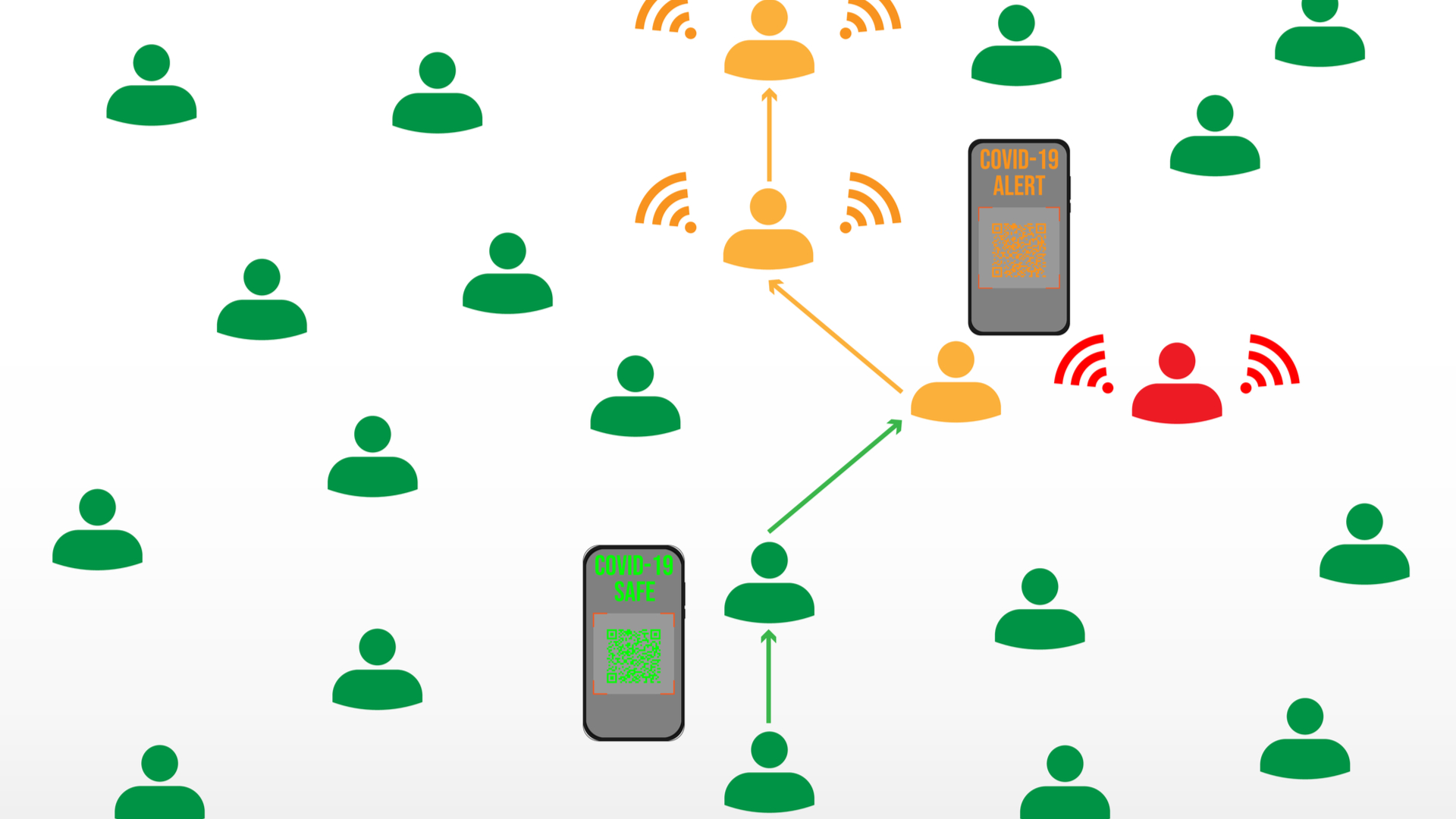

Scotland will launch its own contact-tracing app

Scotland will launch its own contact-tracing appNews The Scottish government says the app will arrive in the autumn and will not ask users to reveal personal information

-

Linux Foundation open-sources coronavirus tracing apps

Linux Foundation open-sources coronavirus tracing appsNews The projects, based on the Google and Apple API, aim to support public health contact tracing efforts

-

Video conferencing service StarLeaf sees a 947% surge in UK usage

Video conferencing service StarLeaf sees a 947% surge in UK usageNews CEO Mark Richer believes this trend will continue long after the pandemic is over

-

UK's contact-tracing app will be ready in "two to three weeks"

UK's contact-tracing app will be ready in "two to three weeks"News NHSX CEO says app will be "crucial" in easing lockdown restrictions

-

NHS starts trial of machine learning system to predict demand

NHS starts trial of machine learning system to predict demandNews CPAS was developed by NHS Digital and a team of researchers from the University of Cambridge