Who owns the data used to train AI?

Elon Musk says he owns it – but Twitter’s terms and conditions suggest otherwise

For decades, the fields of rocket science and brain surgery have been cited as endeavors that present almost unimaginable levels of complexity. Now we might want to add another tricky job to the list: managing Twitter – or X as it’s now known.

Since Elon Musk dropped $44bn and took control of Twitter at the end of last year, it hasn’t gone well. The CEO – who let’s not forget, is heavily invested in both rocket and neural science – has seen the value of the social network plummet. One study found that more than half of Twitter’s top 1,000 advertisers have given up on the platform since his takeover.

When Microsoft announced it would be pulling advertising from the platform, reportedly because it refused to pay hiked API-access fees, Musk responded with a threat: “They trained illegally using Twitter data. Lawsuit time.”

He’s arguing that generative AI models such as the ones created by Microsoft and its partner OpenAI, the firm behind ChatGPT, were getting a free ride on Twitter’s data. Large language models (LLMs) that power AI tools have been ‘trained’ on text taken from across the internet. This could conceivably have included data from Twitter. Now Musk wants his pound of flesh – but who owns the data once it’s out on the internet?

The good, bad, and ugly of web scraping

“There’s so many variables that help to answer whether a specific scraping act is legal or illegal,” says Denas Grybauskas, head of legal at web scraping firm Oxylabs.

His company specializes in writing scrapers – software and tools that automate the work of downloading the contents of a website or individual webpage then extracting and organizing the data. It’s like saving a webpage on your computer but automated and on a mass scale.

Scrapers can be used for both good and bad. For example, it’s easy to imagine a retailer may wish to scrape real-time prices from a competitor, to keep tabs on them. Or perhaps an academic may wish to download thousands of social media posts to analyze what people are talking about. But scrapers can also be used for pirating content or infringing intellectual property (IP). Either way, it’s the same sort of technical process that companies such as OpenAI have performed to acquire the data on which to train their AI models.

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

At the heart of the dispute between Musk and Microsoft is both a legal question and a moral one: what content scraping counts as fair game? Grybuskas draws the line at what he calls “public data”.

“There are some exceptions, but legitimate scrapers try to take public data because it’s open to everyone,” he says. “And web scraping is just a smart way of gathering data. When it comes to Twitter, Twitter is a public website.”

The distinction between public and private is, in his view, relatively straightforward as it is both legally and functionally demarcated by the nemesis of scrapers everywhere: the login box and the captcha form.

“If I have to log in to see data, that also means that I have to accept terms of service of the website, which usually precludes scraping activities,” says Grybauskas.

Legally speaking, there can be further complications. Even if scrapers just stick to public data, not all data is created equal. “Maybe it was personal data, [which adds] another layer of legal implications,” he says. “Maybe Musk is not right in saying the scraping was illegal, but maybe Microsoft breached privacy laws or GDPR, if the data involved names and [other personal data].”

RELATED RESOURCE

This on demand webinar explores the state and potential of AI in the financial services industry

WATCH NOW

Amusingly, even if Musk does have a point about the legality of scraping, he may not own the Twitter data he alleges Microsoft used. According to the Twitter terms of service: “You retain your rights to any Content you submit, post or display on or through the Services. What’s yours is yours — you own your Content”.

So, it could be the users of Twitter, not its billionaire owner, who have a case to press. “Of course, they [Twitter] license the data from the users, but you can raise the question of whether Twitter and Musk would be the right plaintiffs to sue Microsoft,” says Grybuskas.

Is public data fair game for AI training?

More broadly, scrapers have been around since the dawn of the internet, as fundamentally they are just software tools that shuffle data from one place to another. But there is a real tension between content creators and the scrapers. The rise of generative AI that requires vast amounts of data merely increases that tension. An added complication is that, with generative AI tools, you can generate new creative works trained on scraped data that someone else created.

However, some experts believe there’s little legal distinction between the AI tools and what’s gone before. “Google search results, for the most part, are full of copyright infringements,” says Dan Purcell, founder and CEO of Ceartas, a company that tracks stolen images for social media influencers and creators.

“When you just look at them for what they are, Google and ChatGPT are pretty much the same thing,” he adds. “Google is still pulling a whole load of stuff in that it probably shouldn’t be, because it doesn’t understand context. That’s the problem. They do the same thing.”

In his view, to protect against AI training, he argues models such as GPT need a system analogous to Google, where rights holders can request certain content be removed. “The same thing needs to happen with ChatGPT,” he says. “It needs to be told, ‘hey, you shouldn’t be saying this, and you shouldn’t be providing this information. This is not your information to provide. This is copyright. This is plagiarism’.”

Whether or not Musk ever provides any evidence to support his claims about Microsoft, the battle between the scrapers and the content owners will continue to rage. And the calls for tighter controls on which data AI models can use will no doubt become louder. But this could be a double-edged sword.

“If AI models and AI companies were prohibited from using scraped data, the innovation would be way, way slower,” says Grybauskas. “It’s not always possible to get licenses and you need vast amounts of data to properly train AI models.”

-

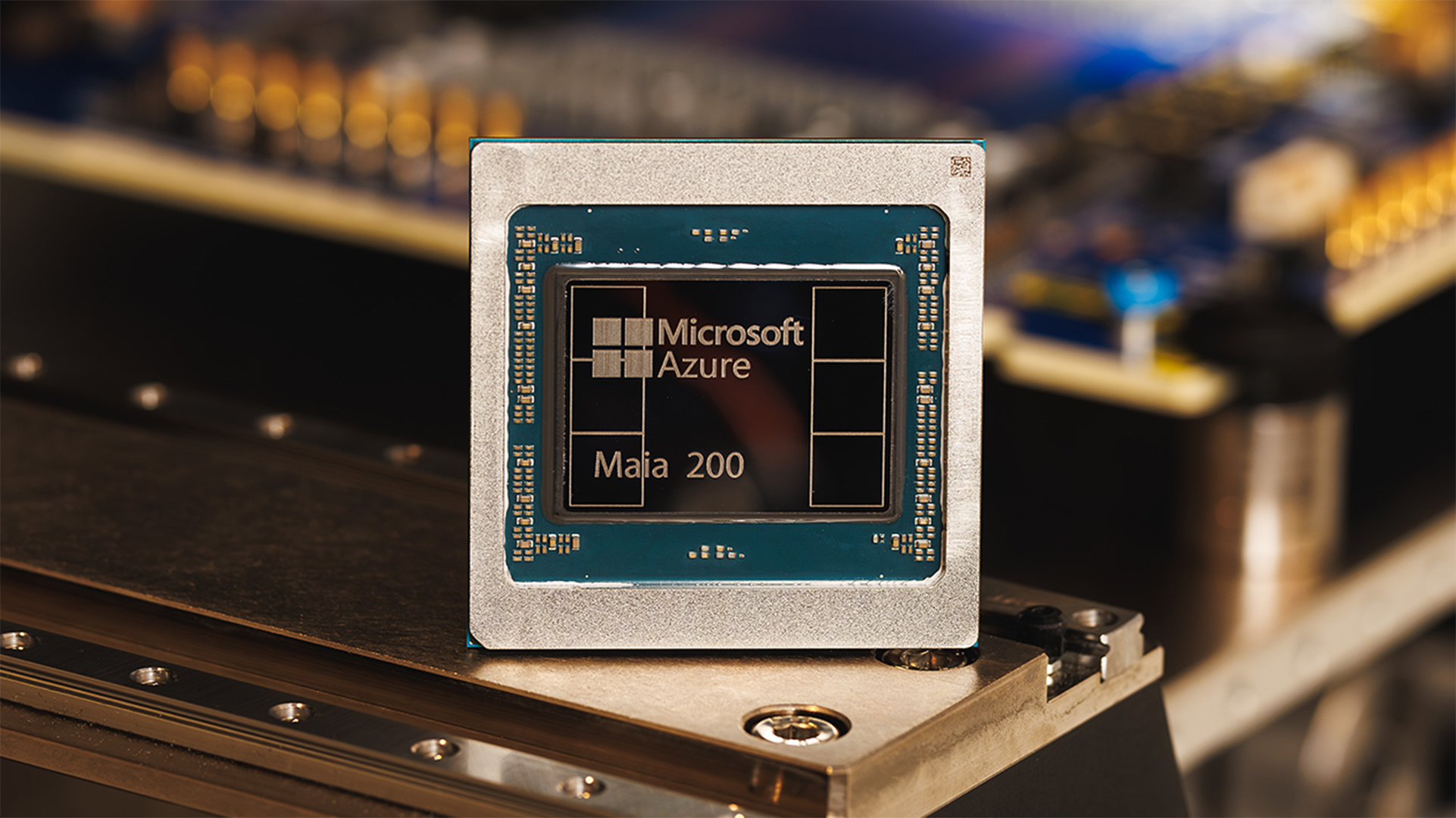

Microsoft unveils Maia 200 accelerator, claiming better performance per dollar than Amazon and Google

Microsoft unveils Maia 200 accelerator, claiming better performance per dollar than Amazon and GoogleNews The launch of Microsoft’s second-generation silicon solidifies its mission to scale AI workloads and directly control more of its infrastructure

-

Infosys expands Swiss footprint with new Zurich office

Infosys expands Swiss footprint with new Zurich officeNews The firm has relocated its Swiss headquarters to support partners delivering AI-led digital transformation

-

Elon Musk confirms Twitter CEO resignation, allegations of investor influence raised

Elon Musk confirms Twitter CEO resignation, allegations of investor influence raisedNews Questions have surfaced over whether Musk hid the true reason why he was being ousted as Twitter CEO behind a poll in which the majority of users voted for his resignation

-

Businesses to receive unique Twitter verification badge in platform overhaul

Businesses to receive unique Twitter verification badge in platform overhaulNews There will be new verification systems for businesses, governments, and individuals - each receiving differently coloured checkmarks

-

Ex-Twitter tech lead says platform's infrastructure can sustain engineering layoffs

Ex-Twitter tech lead says platform's infrastructure can sustain engineering layoffsNews Barring major changes the platform contains the automated systems to keep it afloat, but cuts could weaken failsafes further

-

‘Hardcore’ Musk decimates Twitter staff benefits, mandates weekly code reviews

‘Hardcore’ Musk decimates Twitter staff benefits, mandates weekly code reviewsNews The new plans from the CEO have been revealed through a series of leaked internal memos

-

Twitter could charge $20 a month for 'blue tick' verification, following Musk takeover

Twitter could charge $20 a month for 'blue tick' verification, following Musk takeoverNews Developers have allegedly been given just seven days to implement the changes or face being fired

-

Twitter reports largest ever period for data requests in new transparency report

Twitter reports largest ever period for data requests in new transparency reportNews The company pointed to the success of its moderation systems despite increasing reports, as governments increasingly targeted verified journalists and news sources

-

IT Pro News In Review: Cyber attack at Ikea, Meta ordered to sell Giphy, new Twitter CEO

IT Pro News In Review: Cyber attack at Ikea, Meta ordered to sell Giphy, new Twitter CEOVideo Catch up on the biggest headlines of the week in just two minutes

-

Jack Dorsey resigns as Twitter CEO

Jack Dorsey resigns as Twitter CEONews CTO Parag Agrawal takes the reins as Dorsey also plans to leave board position