FCC is supplying malware-loaded phones to low-income users

Budget handsets are pre-installed with malicious apps that leak data to Chinese hackers, report finds

A federal programme supplying cheap mobile phones to low-income US citizens has been accidentally selling handsets loaded with Chinese malware that can’t be removed.

The UMX U686CL handset, available at just $35 under the FCC’s Lifeline Assistance programme, is being distributed with pre-loaded software that creates backdoors that could potentially leak user data.

The UMX handsets, distributed through Virgin Mobile’s Assurance Wireless scheme, are bundled with an app called ‘Wireless Update’. Researchers discovered this is an offshoot of Adups, a Chinese firm known for harvesting user data and building auto-installers.

Wireless Update, incidentally, is the only way users can update the handset’s operating system.

The phone’s own Settings app, too, functions as a cleverly disguised piece of malware that cannot be removed or else the devices becomes entirely unusable.

“Pre-installed malware continues to be a scourge for users of mobile devices,” said senior malware intelligence analyst with Malwarebytes, Nathan Collier.

Researchers only “scratching the surface” of a pervasive Android bloatware issue Privacy International claims most Android apps share data with Facebook without user consent Thousands infected with malware that 'reinstalls itself' Google's Adiantum aims to bring encryption to low-end smartphones and devices

“But now that there’s a mobile device available for purchase through a US government-funded program, this henceforth raises (or lowers, however you view it) the bar on bad behaviour by app development companies.”

Sign up today and you will receive a free copy of our Future Focus 2025 report - the leading guidance on AI, cybersecurity and other IT challenges as per 700+ senior executives

“Budget should not dictate whether a user can remain safe on his or her mobile device.”

Phone manufacturers paying to install pre-loaded apps containing potentially harmful code is a worrying trend, increasingly highlighted by security experts.

Researchers highlighted their concerns in a paper last year, identifying variants of well-known malware families loaded into pre-installed apps supplied in predominately low-end range phones.

Malwarebytes was first alerted to complaints around government-issued phones from its users in October 2019, before purchasing a UMX U686CL to investigate further.

After learning that Wireless Update was flagged with a malicious detection name, Malwarebytes informed Virgin’s Assurance Wireless scheme of the potential dangers - but did not hear back.

Wireless Update begins auto-installing apps the moment users sign into their device but doesn’t ask users for consent for any installations. While the app installs are initially malware-free, the apps are added with no notifications or attempts to seek user consent.

This arrangement, researchers argue, opens the door for malware to be unknowingly installed in future updates to any of the apps automatically added by Wireless Update.

To compound the issue, the malicious Settings app serves as the dashboard from which the phone’s settings are changed, and cannot be removed without bricking these devices. The malware also shares characteristics with other known Trojans.

The Settings app contains a string within its code that, when decoded, revealed a hidden library file. When activated, this is loaded into the device’s memory before dropping a further piece of malware known as HiddenAds.

RELATED RESOURCE

Collier added there’s currently no way to uninstall pre-installed apps on devices like the UMX, and doing so, in any case, would lead to dire consequences for usability.

Uninstalling Wireless Update, for example, could lead users to miss out on critical operating system patches, given it’s the only way to update the phone’s software. Removing Settings, meanwhile, would brick the phone entirely.

Although the UMX situation adds a unique dimension to phones that come with pre-installed malware, given these are supplied by the US government, it’s not entirely uncommon.

Research published in 2017 showed a plethora of Android devices, from device makers including Samsung, LG, Asus, Opp, and Xiaomi, among others, were packaged and sold with pre-installed malware.

Keumars Afifi-Sabet is a writer and editor that specialises in public sector, cyber security, and cloud computing. He first joined ITPro as a staff writer in April 2018 and eventually became its Features Editor. Although a regular contributor to other tech sites in the past, these days you will find Keumars on LiveScience, where he runs its Technology section.

-

Blackpoint Cyber and NinjaOne partner to bolster MSP cybersecurity

Blackpoint Cyber and NinjaOne partner to bolster MSP cybersecurityNews The collaboration combines Blackpoint Cyber’s MDR expertise with NinjaOne’s automated endpoint management platform

-

Busting nine myths about file-based threats

Busting nine myths about file-based threatsWhitepaper Distinguish the difference between fact and fiction when it comes to preventing file-based threats

-

The Total Economic Impact™ of the Intel vPro® Platform as an endpoint standard

The Total Economic Impact™ of the Intel vPro® Platform as an endpoint standardWhitepaper Cost savings and business benefits enabled by the Intel vPro® Platform as an endpotnt standard

-

The Total Economic Impact™ of IBM Security MaaS360 with Watson

The Total Economic Impact™ of IBM Security MaaS360 with WatsonWhitepaper Cost savings and business benefits enabled by MaaS360

-

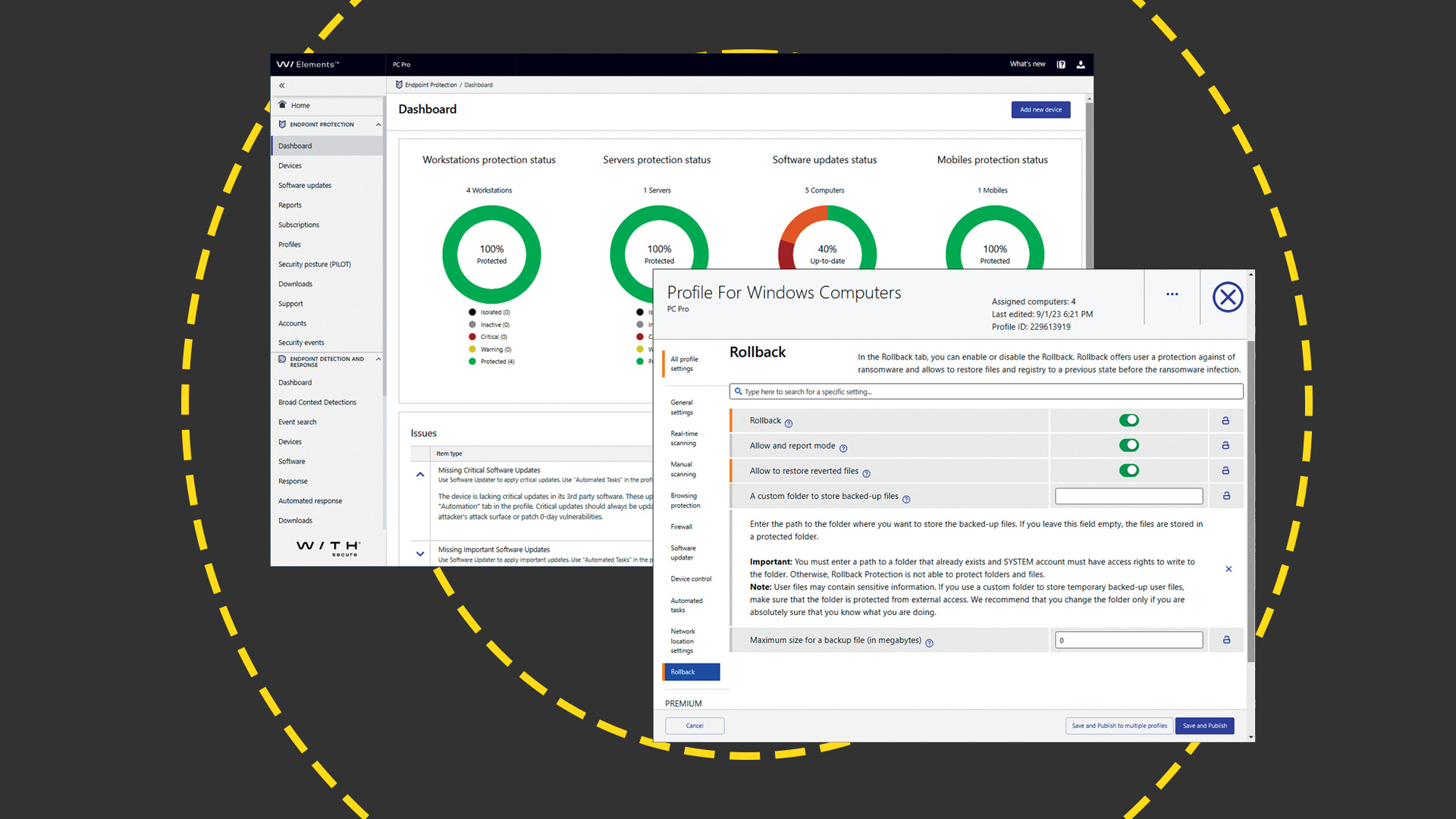

WithSecure Elements EPP and EDR review: Endpoint protection on a plate

WithSecure Elements EPP and EDR review: Endpoint protection on a plateReviews An affordable cloud-managed solution with smart automated remediation services

-

KuppingerCole leadership compass report - Unified endpoint management (UEM) 2023

KuppingerCole leadership compass report - Unified endpoint management (UEM) 2023Whitepaper Get an updated overview of vendors and their product offerings in the UEM market.

-

The Total Economic Impact™ of IBM Security MaaS360 with Watson

The Total Economic Impact™ of IBM Security MaaS360 with WatsonWhitepaper Get a framework to evaluate the potential financial impact of the MaaS360 on your organization

-

Unified endpoint management software vendor assessment

Unified endpoint management software vendor assessmentWhitepaper Make positive steps on your intelligent automation journey